Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

Professor Emeritus

The University of Akron

Audiologists observe the impact of stigma on hearing loss (HL stigma) on a regular basis, and yet we haven’t addressed it much as a counseling issue. HL stigma can be a complicated experience: for many patients, developing hearing loss can itself be stigmatic (associated with negative stereotypes of aging). And as we know, the added prospect of hearing aids can compound the stigma further. Recent research (David et al. 2018) supports this long-standing observation: that hearing aids can be “central to the stigmatic experience,” which is why we need to attend to “the importance of these devices for psychological wellbeing” (p. 133).

From a counseling perspective, we have to acknowledge that HL stigma has negative power and should be addressed. Stigma has been consistently found to impede help-seeking (e.g., Gagné et al., 2011; Heijnders & van der Meij, 2006; Wallhagen, 2009), so our challenge is to address it openly and therapeutically. This article will provide a basic background regarding the development of stigma, and suggestions on how to address stigma in clinic.

Stigma Develops in Stages

Corrigan et al. (2006) describe stigma development as a socially-constructed three-stage process:

1st stage: Stereotype Awareness, wherein we are aware of society’s negative beliefs about a health condition or disability: My grandmother says all of her friends are losing their hearing. She says they always seem confused, and she doesn’t enjoy their company anymore.

2nd stage: Stereotype Agreement, wherein we concur and endorse these negative beliefs, developing our own prejudice: When I visited my grandmother, I could see why she doesn’t enjoy her friends these days. They are in their own world and have no idea what anyone else is talking about.

3rd stage: Self-Congruence or Self-Stigma, wherein we internalize society’s negative attitudes and apply them to ourselves, risking adverse effects on self-concept and personhood: I am having the same hearing problem my grandmother used to complain about. It’s so humiliating.

The final stage – self-stigma – includes self-rejection, a belief in a diminished self, and shame, wherein an individual feels “disqualified from full social acceptance” (Goffman, 1963, p. 9). Weiss et al. (2006) describes self-stigma as a “hidden burden” – our challenge is to help patients discuss that burden and perhaps free oneself from it.

Rosenstock, 1974

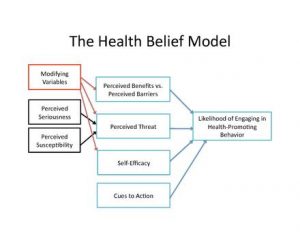

Our take-away: as described above, stigma is a belief, which in itself presents a challenge. Because of our scientific base, audiologists don’t pay much attention to beliefs, but we should. After all, common objections to hearing devices – the impact on self-image and self-identity, cosmetic sensitivity, the certainty of social rejection – are beliefs, not facts. We may be familiar with The Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974), created as a means to predict health-promoting behaviors (e.g., Saunders et al., 2013), but it has yet to impact clinical practices.

Preparing Ourselves

Before we respond to a patient’s perception of stigma, we must be comfortable talking about it. For instance, we may worry about the “elephant in the room” phenomenon:  should we “go there?” We may think that talking about it will increase a patient’s self-stigma, yet if we don’t talk about it, we can be fairly sure it will not resolve on its own.

should we “go there?” We may think that talking about it will increase a patient’s self-stigma, yet if we don’t talk about it, we can be fairly sure it will not resolve on its own.

As applied to audiologic counseling, we aim to help patients consider changing their negative beliefs about hearing loss and hearing help (Clark & English, 2019). Consider the following dialogue: how did the audiologist help the patient transcend stigma and move forward?

A Self-Stigma Conversation

Audiologist: Mr. Petry, now that we’ve compared your initial concerns to your test results, we can shift gears and talk about next steps. You mentioned upfront that you just wanted information but had no interest in hearing aids – could you expand on that?

Mr. Petry: Wait, are you saying I need hearing aids? I really don’t want to!

Audiologist: Because ….?

Mr. Petry: (getting agitated) Because … hearing aid users are feeble and old. I don’t want to be that kind of person.

Audiologist: Are you thinking of someone in particular – someone you know? (Patient nods.) What might it seem like from his/her point of view?

Mr. Petry: Sure, there’s my old pal Jim. He doesn’t seem to mind how his hearing aids look – but I do. Why advertise your problems like that? No one wants to look weak.

Audiologist: OK. It sounds like he doesn’t see it that way, though. If you asked him, how might he describe hearing aid use?

Mr. Petry: I know him pretty well; I think he’d say he doesn’t care about what other people think.

Audiologist: Have you ever wondered how you developed your reaction to hearing aids?

Mr. Petry: Just from what people say, I guess.

Audiologist: Other people really can influence us, and often we don’t even notice it. My concern is this: your thoughts on amplification are keeping you from improving the problems you initially mentioned. Is there another way you could think about amplification that would make you feel strong instead of weak?

Mr. Petry: Well, I normally face my problems head on – like Jim, actually. It probably wasn’t easy for him to become a hearing aid user but he did it anyway. If he can do it, so can I.

Audiologist: Then we’ll tap into your past history of successful problem-solving. You might experience mixed feelings along the way, but we’ll keep talking about it. I agree, it’s not easy.

Breaking Through Self-Stigma

What Happened Here?

The audiologist attempted to:

- Accept the negative beliefs without judgment.

- Shift from “stereotype agreement” (“that kind of person”) to a specific relationship (Jim) and asked the patient to imagine a different perspective.

- Validate that different perspective (“sounds like he doesn’t see it that way”) and encouraged the patient to again consider his friend’s situation.

- Ask the patient to consider the source of his stigmatic belief.

- Ask the patient to reframe his belief (“Is there another way you could think about” hearing aids, like your friend does?)

- Validate his past history of successful efforts.

These steps helped the patient examine unquestioned negative beliefs about hearing aids and consider alternative points of view and choices.

Three Things Didn’t Happen

The audiologist took pains not to:

- Discount or overrule expressed self-stigma (“you shouldn’t feel that way/you shouldn’t let that belief hold you back”). Once a patient verbalizes a position, it’s hard to back down (Gardner, 2004).

- “Upshift,” as described by Goulston (2010): “Most people upshift when they want to get through to other people. They persuade. They encourage. They argue. They push. And in the process, they create [even more] resistance” (p. 4)

- Use the words stigma, stereotype, or beliefs, to avoid putting the patient on the defensive.

Not a One-Time Conversation

Developing stigma is a process; transcending it will also be a process. We should remind ourselves to continue the conversation in subsequent appointments regarding changes in perception, beliefs, acceptance. Why? Because change is hard! “Stigma is powerfully reinforced by culture and its effects are not easily overcome by the coping actions of individuals” (Heijinders & van der Meij, 2006, p. 356).

Developing stigma is a process; transcending it will also be a process. We should remind ourselves to continue the conversation in subsequent appointments regarding changes in perception, beliefs, acceptance. Why? Because change is hard! “Stigma is powerfully reinforced by culture and its effects are not easily overcome by the coping actions of individuals” (Heijinders & van der Meij, 2006, p. 356).

Also: Invite the Conversation

Doherty (2016) reminds us, “Our patients will likely be sensitive to potential stigma, even if they do not mention it.” As a matter of course, we can routinely bring it up ourselves: “Sometimes patients worry about [appearance, societal reactions, etc.]. What are your thoughts? Any qualms?”

Conclusion

Talking about stigma certainly qualifies as a difficult conversation! Our skill in doing so could make the difference in patient decisions, but we have had virtually no guidance. We need to develop our own guidance, and share our work with the profession.

References

Clark & English (2019). Counseling-infused audiologic care. Inkus Press/Amazon.com

David, D., Zoizner, G. & Werner, P. (2018). Self-stigma and age-related hearing loss: A qualitative study of stigma formation and dimensions. American Journal of Audiology, 27, 126-136.

Doherty J. (2016). New thoughts on hearing loss and stigma.

Gardner, H. (2004). Changing minds: The art and science of changing our own and other peoples’ minds. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. NY: Simon & Schuster.

Goulston, M. (2010). Just listen: Discover the secret to getting through to absolutely anyone. New York: AMACOM.

Heijnders, M., & van der Meij. (2006). The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 353-363.

Saunder, G., Frederick, M.T., Silverman, S. & Papesh, M. (2013). Application of the health belief model: Development of the hearing beliefs questionnaire (HBQ) and its associations with hearing health behaviors. International Journal of Audiology, 52(8), 558-567.

Wallhagen, M. (2009). The stigma of hearing loss. The Gerontologist, 50(1), 66-75.