Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

The University of Akron/NOAC

Even the most family-centric audiologists can find themselves on a different page than parents on the topic of consistent amplification. One reason may be our training: we have been taught to emphasize the relationship between amplification and the development of speech and language. While true, it is also possible that families are not following our logic. In fact, logic may not be part of their reactions at all. At the moment, families’ uppermost concern may be centered around their child’s emotional development: Will our baby be happy? Feel safe? Will she know we love her?

Families intuitively want to nurture and bond with their baby, and hearing actually supports that process. But even as hearing is taken for granted, so are the effects of hearing on parent-child bonding. Our challenge is to align our communication with what families value, and be comfortable talking to parents about the importance of their child hearing “the love in their voice.”

Following are two topics: A brief summary of selected research describing listening skills in infants with no hearing loss, and then a suggestion on how help families use amplification for the express purpose of bonding with their baby. We can think of this process as “auditory imprinting.”

Babies are Born Listening

Babies hear their mother’s voice for many weeks before they are born, and after birth are ready to listen for mom at surprisingly sophisticated levels. For instance, Querleu et al. (1984) tested 25 newborns, all less than 2 hours old, by presenting recordings of five women speaking the babies’ names. One voice was the baby’s mother, and four voices were unknown to the baby. Three observers independently rated each baby’s reaction to each voice as nonexistent, weak, or strong. They found that when the babies heard their mother’s voice, they had strong reactions almost half the time. Not a robust finding, but remember, the babies were only 2 hours old but already telling us that mom’s voice is meaningful to them.

A classic study by DiCasper and Fifer (1980) found that not only does baby recognize mother’s voice, but actively prefers it to others. The researchers recruited 10 mothers to record reading from Dr. Seuss immediately after they delivered their babies (agreed, that alone is amazing). Their newborns were later placed under headphones before they were 24 hours old. After obtaining baseline sucking rates (using nonnutritive nipples and computer software to calculate rates per minute), the researchers presented recordings of mother and other women reading. Babies quickly learned they could control the input: when they sucked on the nipple at a rate lower than their baseline, that action would deliver an unfamiliar female voice. When they increased their sucking rate, they would hear their mother’s voice. Once they learned the relationship between sucking rates and voice input, they consistently “chose” mother using an increased rate. Think about it: a 1-day old baby is capable of mastering an elementary lesson in cause-and-effect based on what he or she heard, and it is mom’s voice that facilitates that learning.

We know, then, that babies prefer their mother’s voice, but even more than just voice is the nature of the voice. We are quite familiar with motherese, which employs a higher pitch, sing-song intonations, words that are evenly spaced, and slower rates. When mother uses these vocal characteristics, the baby is captivated and will increase his/her “looking time” while listening. To keep looking means the baby is starting to learn to pay attention, which is key to all learning – one cannot learn without attending for some amount of time.

We know, then, that babies prefer their mother’s voice, but even more than just voice is the nature of the voice. We are quite familiar with motherese, which employs a higher pitch, sing-song intonations, words that are evenly spaced, and slower rates. When mother uses these vocal characteristics, the baby is captivated and will increase his/her “looking time” while listening. To keep looking means the baby is starting to learn to pay attention, which is key to all learning – one cannot learn without attending for some amount of time.

“Motherese” input is so meaningful to babies, it doesn’t matter if it comes from someone other than mother. Fernald’s 1985 study included 48 infants, all 4 months of age, who were presented two types of speech stimuli: “adult directed” (adult-to-adult conversation), and “infant directed” (motherese). The voices they listened to were unfamiliar females; however, their responses, measured by head turns, indicated they were more interested in motherese than adult-directed speech, even when it came from a stranger.

From studies using soft nets of electrodes (e.g., Grossman, 2007), we know that babies are also able to perceive the differences in timing patterns, pitch, intensity, and emotional intent. For instance, if a steady set of low pitches is presented, and then one high pitch is presented, the brain activity changes, indicating awareness that something different happened.

Babies are not able to understand words yet, of course, but they are sensitive to the intonation of our voice. The sing-song nature of Infant Directed Speech naturally leads us to actual songs, specifically, music created with babies in mind: lullabies.

The effects of singing lullabies to babies has been measured extensively (e.g., see Baker & Mackinlay, 2006), recently in relationship to the release of hormones in different situations. As lullabies are being sung, the chemical changes that occur in both the singer and the baby create a sense of well-being. While sharing space and time together, both parent and child feel calmed and connected. It also gives the singer some protected “you-and-me time” to observe how baby reacts to different ways of being held, how long it takes to settle down from different situations, what makes the baby smile, and other behaviors that help parent understand baby.

To summarize this section: when a child is born with no hearing loss, we know:

- Babies recognize mom’s voice (2 hours old)

- Babies choose listening to mom’s voice more than other women’s voices (1 day old)

- Babies are especially responsive to Infant-Directed Speech and lullabies.

We also know that babies can perceive differences in virtually every speech characteristic. Researchers generally conclude that infants are biologically predisposed to respond to the human voice.

How to Translate Research to Families?

Parents may not be terribly interested in the details of these kinds of studies, but they are might appreciate learning that they nurture with their voice, that their voices matter to baby and promote the parent-child bonding process.

We have reviewed how babies are born “primed to hear,” especially to hear/listen for the human voice, and that they quickly start using auditory information to inform them about their world. Now we will focus on the baby with a hearing loss. Optimally, the HL is identified very early and treated with amplification in a timely fashion. However, there is still hard work ahead, specifically the family’s journey toward consistent use of amplification. This work is all on parents’ shoulders but we still need to ask ourselves, how can we help?

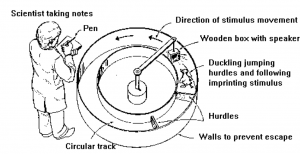

Recall the classic imprinting experiment where ducklings latch on to the first thing they see. For instance, a researcher arranges for a duckling to hatch in a pen with no mother duck around. However, in the pen hangs a boot on a short pole, and when a motor activates the boot to move, the duckling adopts the boot as its mother – forever.

For humans, that bonding experience depends less on what is seen (since vision is weak for months), and more on other inputs: (1) how a baby is held (with comfort and delight? with stiffness and resentment?), (2) whether needs are meet (food, warmth, dryness, secure positioning in space) and (3) what the baby hears. Our voices help a baby feel calm, safe, and reassured, and the people whose voices babies hear are the people babies learn to count on, trust, love.

For humans, that bonding experience depends less on what is seen (since vision is weak for months), and more on other inputs: (1) how a baby is held (with comfort and delight? with stiffness and resentment?), (2) whether needs are meet (food, warmth, dryness, secure positioning in space) and (3) what the baby hears. Our voices help a baby feel calm, safe, and reassured, and the people whose voices babies hear are the people babies learn to count on, trust, love.

Let us speak directly to the “family work” of parent-child bonding. Among the variables that help parents and children “fall in love,” hearing plays an important part! We can help families remember that hearing parents’ reassuring voices, hearing infant-directed speech, and hearing lullabies helps the child feel secure and comforted. Amplification is a tool; bonding is the goal. A handout has been developed to support this conversation; early feedback on its use in the field has been positive but the author would also appreciate hearing from you! (ke3@uakron.edu)

References

Baker F, Mackinlay E. (2006). Sing, soothe, and sleep: A lullabye education programme for first-time mothers. Brit J of Music Ed, 23(2), 147-160.

DeCasper A, Fifer W. (1980). Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. Science, 208 (4448), 1174-1176.

Fernald A. (1985). Four month old infants prefer to listen to motherese. Infant Beh Dev, 8, 181-195.

Grossman T et al. (2005). Infants’ electric brain responses to emotional prosody. NeuroReport, 16(16), 1825-1828.

Querleu D et al. (1984). Reaction of the newborn infant less than 2 hours after birth to the maternal voice. J Gynocol Obstet Reprod, 13(2), 125-134.