Kris Engish, PhD

Kris Engish, PhD

Professor Emeritus, Audiology

University of Akron

Scenario: an audiologist greets a new patient. She introduces herself, gestures towards chairs and, once seated, asks, “Now then … what brings you to our clinic today?” The patient shares recent observations from loved ones about his hearing, expressing some skepticism while acknowledging a small degree of personal concern. The audiologist maintains eye contact, does not interrupt, nods occasionally, takes a few notes, and then stands up. “This is very helpful. Let’s move forward with some testing now.”

Analysis: Did the audiologist listen? Yes, to a limited degree. She did demonstrate “cognitive listening,” a passive process of attending to and processing input.1 But passivity creates a problem: during this encounter, did the patient feel heard? Does it matter? And how does it compare to active listening?

Active Listening = Listening + Engagement

Taking the last question first: active listening is not about listening per se, but about interactivity. (It has been suggested that the term “conversational listening” might be more meaningful.1) While attending to a patient’s narrative, active listeners also verbally respond – with paraphrases, questions, affirmations, requests for clarifications, call-backs to previous topics – to assure patients that they are being heard.2,3

Taking the last question first: active listening is not about listening per se, but about interactivity. (It has been suggested that the term “conversational listening” might be more meaningful.1) While attending to a patient’s narrative, active listeners also verbally respond – with paraphrases, questions, affirmations, requests for clarifications, call-backs to previous topics – to assure patients that they are being heard.2,3

For our listener to feel heard, our reactions and thoughts must be perceptible, via expressions of interest, empathy, respect, and care.4 Our hypothetical audiologist did not convey any of these responses; in fact, as far the patient could tell, she might have been only pretending to listen, pretending to care.

“Feeling Heard” Matters

We know from our own experiences what it is like to not feel heard… a bundle of negative reactions from being ignored or dismissed, resulting in resentment and distrust. In healthcare, these consequences are serious: research indicates that patients who do not feel heard are less likely to adhere to healthcare recommendations.5-8

A New Emphasis on Active Listening

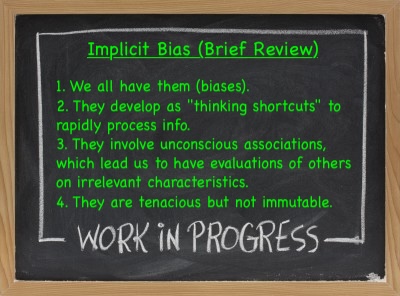

Active listening is not a new concept.9 Interestingly, and surely a sign of the times, it is being reintroduced with the intentional goal of reducing clinician bias.10

11. Smiley (2024)

When persons are internally motivated to work through and past their biases, it helps to focus less on “self” and more on another’s dignity and human desire to be heard.12-19 The commitment to actively listen-empathize-care supports those goals.20

Measuring Active Listening Effectiveness

A new tool called the Feeling Heard Scale (FHS) provides the opportunity to collect feedback regarding our Active Listening efforts.21 The FHS has been evaluated for reliability and validity, and, importantly for busy work settings, is brief. Eight items are measured on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree), to wit: “In this conversation” or “in this meeting”…

- I felt heard by the other person.

- I could say what I really wanted to say.

- the other person was more concerned with him/herself than with what I said.

- the other person listened to what I said.

- the other person tried to put him/herself in my shoes.

- the other person was insensitive to my thoughts and feelings.

- the other person treated me with respect.

- we understood each other.

There is also a single-item alternative to the full scale: “In this conversation, I felt heard by the other person.”

The manual on how to use the FSH22 can be found here (permission granted by the author).

Conclusion: Engaging in active/conversational listening rather than mere “data processing” humanizes the patient, the clinician, and the process. There are many reasons why our responsiveness can lag (fatigue, distractions, personal challenges). There are also many reasons to continue striving for equitable treatment regardless of interpersonal differences. The FHS has not yet been evaluated for clinical use — but what an opportunity for audiology to take the lead, given our commitment to listening as well as hearing!

References

- Collins HK. (2022). When listening is spoken. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101402.

- Nemic PB et al. (2017). Can you hear me now? Teaching listening skills.Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 40(4), 415-417.

- Thistle JJ, McNaughton D. (2015). Teaching active listening skills to pre-service speech-language pathologists: A first step in supporting sollaboration with parents of young children who require AAC.

- Adams K et al. (2012). Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Pt Educ Counsel, 89, 44–50.

- Davies C et al. (2024). Factors that support children and young people to express their views and to have them heard in healthcare: An inductive qualitative content analysis. J Child Health Care, 0(0) 1–14.

- Edelen MO et al. (2022). A novel scale to assess palliative care patients’ experience of feeling heard and understood. J Pain Symptom Mgmt, 63(5), 689-698.

- Shafran-Tikva S, Kluger AN. (2018). Physicians’ listening and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with diabetes. Int J of Listening 32, 140–149.

- Stewart M et al. (2024). Patient-centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method (4th ed.) Abington, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press.

- Rogers CR, Farson RE. (1957). Active listening. Industrial Relations Center, University of Chicago.

- Shelton JN et al. (2023). Responsiveness in interracial interactions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53,101653

- Smiley CJ. (2024). Overcoming the implicit bias shortcut. J Calif Dental Assn, 52(1).

- Bamberg K, Verkuyten M. (2022). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice: a person-centered approach. J Social Psych, 162(4), 435-454. DOI:10.1080/00224545.2021.1917498

- Charlesworth TES, Banaji MR. (2019). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. Long-term change and stability from 2007 to 2016. Psychological Sci, 30(2), 174-192.

- Charlesworth TES, Banaji MR. (2021). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: II. Long-term change and stability, regardless of group membership. Am Psych, 76(6), 851–869.

- Charlesworth TES, Banaji MR. (2022). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: IV. Change and stability from 2007 to 2020. Psychological Sci, 33(9), 1347-1371.

- Itzchakov G et al. (2020). Can high quality listening predict lower speakers’ prejudiced attitudes? J Experimental Social Psych, 91, 104022

- Itzchakov G et al. (2024). Perceiving others as responsive lessens prejudice: The mediating roles of intellectual humility and attitude ambivalence. J Experimental Social Psych, 110, 104554

- LaCosse J, Plant EA. (2020). Internal motivation to respond without prejudice fosters respectful responses in interracial interactions. J Personal Social Psych, 119, 1037–1056.

- Rosenblum M et al. (2022). Detecting prejudice from egalitarianism: Why Black Americans don’t trust white egalitarians’ claims. Psych Sci, 33, 889–905.

- Santoro E, Markus HR. (2023, December). Listening to bridge societal divides. Current Opinion Psyc, 54, 101696

- Roos CA et al. (2023). Feeling heard: Operationalizing a key concept for social relations. PloS One, 18, 11 e0292865.

- Roos FHS User Manual (definitive)

Incongruence hinders our ability to communicate empathy and warm acceptance to persons associated with those biases, and efforts to do so come across as inauthentic.

Incongruence hinders our ability to communicate empathy and warm acceptance to persons associated with those biases, and efforts to do so come across as inauthentic. It would not be unusual for helping professionals to miss the impact of unconscious / implicit bias on congruence – even Carl Rogers seemed to have overlooked it until rather late in his career. Crisp8 recently reported on two video recordings of Rogers’ therapy sessions with two different Black male patients, conducted 5 years apart. The first session from 1979 was described by peers as having a “therapist-centric perspective” (p. 223) with missed opportunities to respond with empathy to the client’s racism experiences and avoiding an exploration about their racial and cultural differences.

It would not be unusual for helping professionals to miss the impact of unconscious / implicit bias on congruence – even Carl Rogers seemed to have overlooked it until rather late in his career. Crisp8 recently reported on two video recordings of Rogers’ therapy sessions with two different Black male patients, conducted 5 years apart. The first session from 1979 was described by peers as having a “therapist-centric perspective” (p. 223) with missed opportunities to respond with empathy to the client’s racism experiences and avoiding an exploration about their racial and cultural differences.

Recently, an additional consideration of patients in the LGBTQ community receiving care in these settings indicated comparably positive PDQ results,12 but also raises a question: why wait until the end stage of healthcare? Social dignity violations (e.g., dismissal, disregard, grouping) routinely occur across a wide range of healthcare encounters throughout a lifetime.13-18 There seems no reason to wait: researchers very familiar with the PDQ have pointed out that the PDQ “can be used by any provider type and in numerous care settings to understand patient values” as a standard of care.19 Since all patients seek relational dignity throughout their lives, extending the PDQ intervention to all patients in all settings seems feasible, or at the minimum to those with historical concerns regarding inequitable care.

Recently, an additional consideration of patients in the LGBTQ community receiving care in these settings indicated comparably positive PDQ results,12 but also raises a question: why wait until the end stage of healthcare? Social dignity violations (e.g., dismissal, disregard, grouping) routinely occur across a wide range of healthcare encounters throughout a lifetime.13-18 There seems no reason to wait: researchers very familiar with the PDQ have pointed out that the PDQ “can be used by any provider type and in numerous care settings to understand patient values” as a standard of care.19 Since all patients seek relational dignity throughout their lives, extending the PDQ intervention to all patients in all settings seems feasible, or at the minimum to those with historical concerns regarding inequitable care.

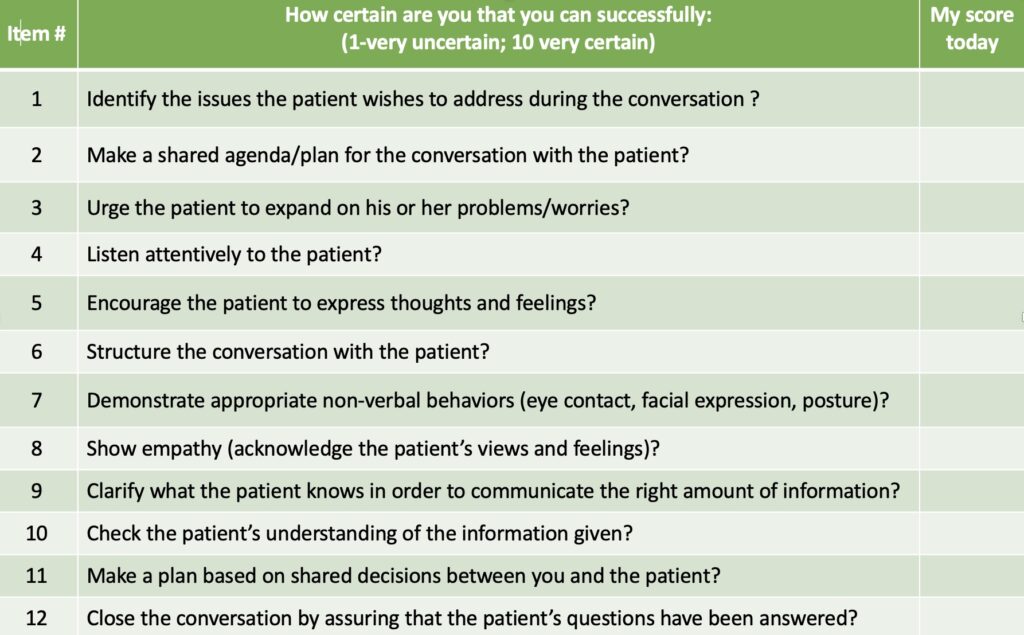

possesses” (1986, p. 391). More simply, “The factors that influence behavior are embedded in the belief that one has the capability to accomplish that behavior” (Klassen & Klassen, 2018, p. 76).

possesses” (1986, p. 391). More simply, “The factors that influence behavior are embedded in the belief that one has the capability to accomplish that behavior” (Klassen & Klassen, 2018, p. 76).

“Clinician presence” may not be familiar to student trainees, but working with the concept might help them recognize the impact we have on patient impressions and patient outcomes. Clinician presence is defined as a “purposeful practice of awareness, focus, and attention with the intent to understand and connect” (emphasis added) with our patient. Core elements include familiar person/patient-centered behaviors and attributes:2

“Clinician presence” may not be familiar to student trainees, but working with the concept might help them recognize the impact we have on patient impressions and patient outcomes. Clinician presence is defined as a “purposeful practice of awareness, focus, and attention with the intent to understand and connect” (emphasis added) with our patient. Core elements include familiar person/patient-centered behaviors and attributes:2

patient’s emotions, attitudes, or problems are directly related to living with hearing loss or balance issues; e.g., reactions to diagnosis, concerns about recommendations, or uncertainties about shared decision-making.

patient’s emotions, attitudes, or problems are directly related to living with hearing loss or balance issues; e.g., reactions to diagnosis, concerns about recommendations, or uncertainties about shared decision-making. emotions or behaviors, develops an over-dependence on the clinician, or continues to use offensive language or “overshares”2 after being asked to stop. Clinicians, of course, may also find themselves crossing a boundary, by becoming overly involved with a patient or oversharing about one’s own personal life.

emotions or behaviors, develops an over-dependence on the clinician, or continues to use offensive language or “overshares”2 after being asked to stop. Clinicians, of course, may also find themselves crossing a boundary, by becoming overly involved with a patient or oversharing about one’s own personal life. coordinated healthcare teams. These days, we may likely find ourselves broaching/being broached about topics other than hearing and balance but still relevant to patient health and safety. Audiologists now inquire about medications that may adversely interact with hearing and balance4-7 and are typically required by law to intervene with a referral when we perceive indications of self-harm or suicide ideation.8 Institutions and states require us to report concerns about child and elder abuse.9,10 Other developments include screening for vision problems,11,12 cognitive and memory concerns,13-15 depression,16-19 and childhood bullying20 – of course not to diagnose but to assume responsibility for overall patient health and safety, and direct those concerns to relevant support systems. And although not directly related to our care, of course we will listen and support patients who are coping with a death in the family and similar life experiences. Person-centered care has replaced disease- or disorder-centered care.

coordinated healthcare teams. These days, we may likely find ourselves broaching/being broached about topics other than hearing and balance but still relevant to patient health and safety. Audiologists now inquire about medications that may adversely interact with hearing and balance4-7 and are typically required by law to intervene with a referral when we perceive indications of self-harm or suicide ideation.8 Institutions and states require us to report concerns about child and elder abuse.9,10 Other developments include screening for vision problems,11,12 cognitive and memory concerns,13-15 depression,16-19 and childhood bullying20 – of course not to diagnose but to assume responsibility for overall patient health and safety, and direct those concerns to relevant support systems. And although not directly related to our care, of course we will listen and support patients who are coping with a death in the family and similar life experiences. Person-centered care has replaced disease- or disorder-centered care.