Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

Professor Emeritus, Audiology

The University of Akron

Audiologists committed to patient-centered counseling are well aware of the importance of humility. As C.S. Lewis once said, “Humility is not thinking less of yourself, it’s thinking of yourself less” – as is our goal in each patient encounter. By word and deed, we communicate respect for the patient’s lived experience, and strive for partnership and service to the patient’s needs, rather than expecting compliance/obedience.

The concept of cultural humility takes us a step further. Communication with patients different than ourselves — by race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, religion, gender, sexual orientation, occupation, abilities – can be inherently complicated. Although not a comfortable idea to consider, we must accept the possibility that we could unintentionally contribute to these complications, potentially resulting in a failure in patient care.

Some Background:

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a 780-page report entitled “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.” In reviewing potential sources of disparity in the United States, including historical segregation and underrepresented minorities in health care settings, the authors included a variable that audiologists can immediately address: our cross-cultural/cross-racial communication skills.

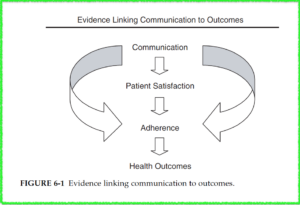

The relationship between communication skills and patient outcomes is succinctly summarized by the figure below:

from Institute of Medicine (2003), p. 200

IOM’s recommended intervention for ineffective communication across race and culture is a familiar one: provide pre-service coursework and in-service training in cultural communication skills. Accordingly, accredited audiology programs in the US are now required to integrate cultural competence into their curricula (Accreditation Commission for Audiology Education, 2016; Council on Academic Accreditation, 2019).

The continuum of skills for cultural competence have been typically listed as awareness, knowledge, sensitivity, and competency (IOM, 2003). However, even before the IOM publication, concerns have been expressed about the limitations of this model:

- The focus of attention is only on “the other” (i.e., reading about, seeking to understand a range of cultures) as a disengaged object of study, which could reinforce an unintended power differential (Foronda, 2020).

- The continuum does not typically emphasize self-awareness or personal change/growth, thereby overlooking the impact each clinician personally has on a clinical encounter, including unrecognized biases and prejudices.

- As an example, Isaacson (2014) describes course outcomes indicating her students perceived themselves as culturally competent, even as their journal reflections revealed many “blind spot” negative stereotypes.

- The word “competency” can imply an endpoint, comparable to mastering tympanometry (i.e., once mastered, the learner moves on to new challenges) rather than life-long learning (Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998).

- Cultural competence also implies “that the healthcare professional has an a priori understanding of the person’s culture before engaging with the patient” (Isaacson, 2014, p. 252).

IOM does stress requisite attitudes such as humility, as well as empathy, curiosity, respect, sensitivity, and awareness of outside influences. Advocates have indicated that the concept of cultural humility (Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998) has not been adequately emphasized, seeing this attribute as a fundamental premise to earning patient trust.

Characteristics of Cultural Humility

- A life-long commitment to cultural competence (no endpoint)

- Assuming no expertise in another’s culture

- Self-reflection, awareness of our own assumptions and prejudices

- Acting to redress the imbalance of power inherent in clinician-patient relationships

- A lack of superiority about one’s own cultural background and experience (Borkan et al., 2008; Foronda, 2020; Hook et al, 2013).

We can safely say that cultural humility is profoundly consistent with the principles of audiologic counseling – in fact, it might seem exactly the same. But we should not be complacent. We may be unaware that our self-perception as patient-centered clinicians may be at odds with a patient’s impressions.

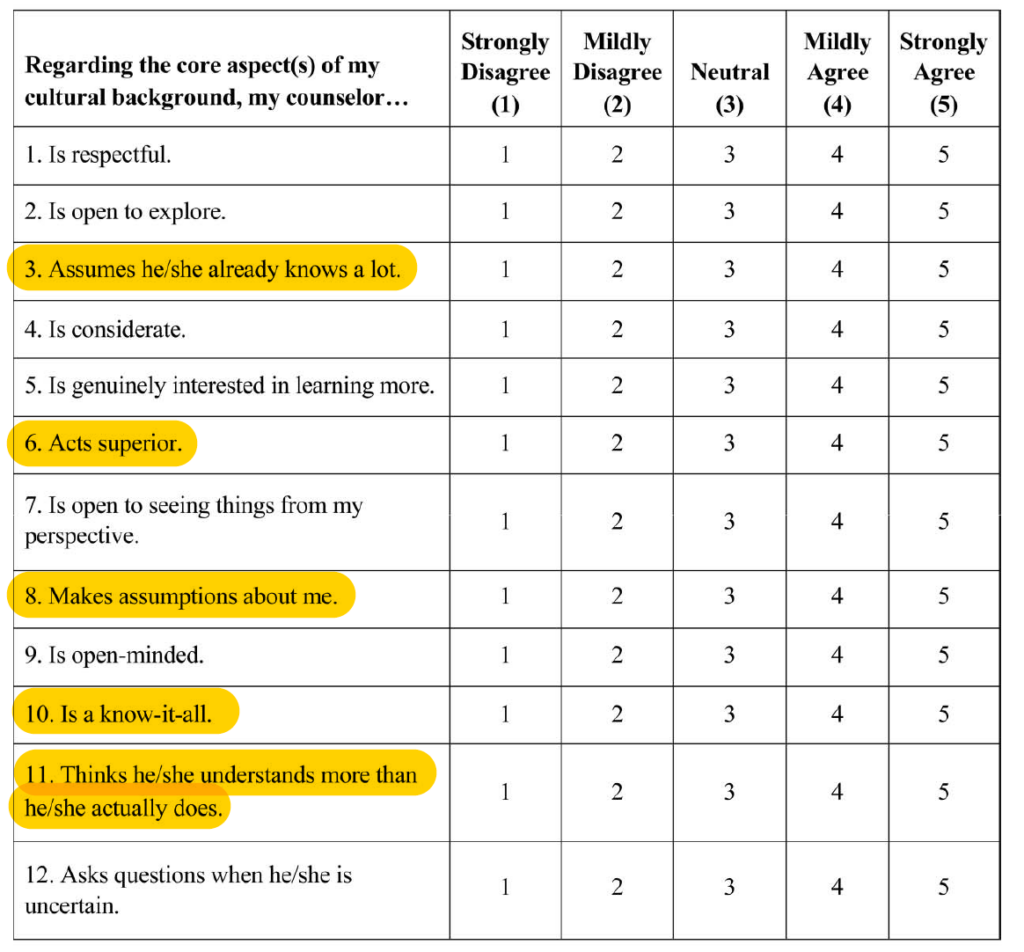

A tool called the Cultural Humility Scale (Hook et al., 2013) was created to measure those impressions. This patient report rates positive and negative behaviors on a 1-5 scale within the context of a person’s cultural background. (Negative behaviors are highlighted.)

from Hook & et al., (2013), p. 366

If we received patient scores of 4 or 5 from the highlighted negative items, we would be devastated. These impressions are not what we intend to convey – but that is precisely the point. We might not realize that an unconscious behavior (an implicit bias) caused a negative reaction (Chapman et al., 2013; Devine, 1989). White et al. (2018) indicate that “Decades of research in social cognitive science show that hidden biases operating largely below the scope of human consciousness influence the way we see and treat others even when we are determined to be fair and objective” (p. 34).

No one is immune from implicit bias. That said, we can learn about and understand our implicit biases in order to manage them. To cross-check our self-perceptions about bias and prejudice, we can explore tools such as an online 10-minute test called the Race Implicit Association Test, view a 12-minute TED talk on implicit bias and discuss it with a colleague, and/or consider the wide range of learning opportunities offered by White et al. (2018, see Appendix).

Conclusion

In all humility, let us appreciate that cross-cultural communication skills do not have an endpoint. Rather, as Campinha-Bacote (2011) suggests, let us think of our pathway as forward steps in awareness, knowledge, sensitivity, and becoming competent throughout our lifetimes.

For more on Cultural Humility:

Part 2: Mitigating Racial Health Disparity with Patient-Centeredness

Part 3: Implicit Bias is a Cognitive Habit We Can Break

Part 4: Perspective-Getting/Radical Empathy

References

Devine, P.G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personal Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18.

Foronda, C. (2020). A theory of cultural humility. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 31(1), 7-12.

Hook, J. N., et al. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 353–366.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117-125,

White, A., et al. (2018). Self-awareness and cultural identity as an effort to reduce bias in medicine. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5, 34–49.