Kris English, PhD

Emeritus Professor of Audiology

The University of Akron

The verb “centering” is becoming popular lately, typically used to spotlight a call for social change. Some examples:

- Headline: “Centering Racial Equity in a New Administration” (Solomon & Roberts, 2020)

- Research article title: “Beyond Seeing Race: Centering Racism and Acknowledging Agency Within Bioethics” (James & Iacopetti, 2021)

- An author’s bio, whose work is focused on “empowering individuals – centering the marginalized – in an effort to create inclusive and compassionate communities” (Burke & Brown, 2021, p. 220)

The concept of “centering” resonates with audiologists committed to person-centered care. Consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s (2001) definition, we strive to provide “care that is respectful and responsive to individual preferences, needs and values; ensuring patient values guide all clinical decisions” (p. 3). A range of clinical skills have been described to help us provide person-centered care, for instance:

- Eliciting, validating patients’ concerns

- Inquiring about, honoring patients’ ideas, expectations

- Assessing impact of symptoms on patients’ quality of life

- Responding to emotional distress with empathic language

- Sharing the decision-making and joint goal-setting processes

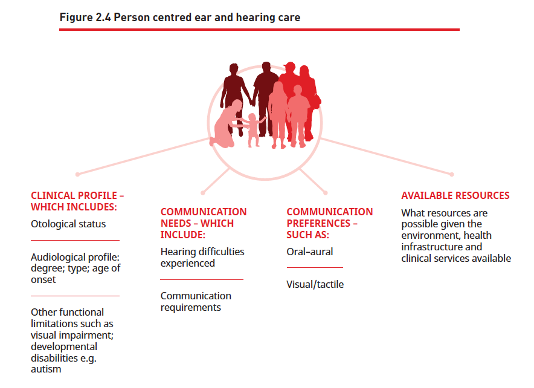

However, there still seems to be a lack of clarity about person-centeredness, most recently represented in the World Health Organization’s (2021) World Report on Hearing. The eagerly-awaited report includes a figure with the caption, “Person-Centred Ear and Hearing Care” (p. 96), listing the care components as obtaining a case history, determining communication needs and preferences, and identifying the patient’s available resources. In this model, each patient’s needs will certainly be individualized, or we could say personalized; however, these data points can be collected and treated with absolutely no application of person-centered care practices as described above.

This confusion in terms is likely due (in part) to the fact that the patient’s voice, the patient’s perception of being “centered,” is not consistently represented in our professional literature. It’s not an unusual situation: in reviewing a set of studies exploring the intersection of person-centeredness and innovation, Makoul (2021) noted that individuals’ perspectives and input were not included. We do have valuable N-of-1 reports from advocates such as Shari Eberts (2020), but we are overdue in developing a person-centered research base that will accurately inform the World Health Organization and other policy influencers. A genuinely person-centered profession centers individuals with hearing loss in its research (e.g., Sharp et al., 2016; Tzelepis et al., 2015).

References

Burke, T., & Brown, B. (2021). You are your best thing. NY: Random House.

Eberts, S. (2020). Person-centered care from a patient’s perspective. Hearing Journal, 73(1), 28.

James J. & Iacopetti, C.L. (2021). Beyond seeing race: Centering racism and acknowledging agency within bioethics. The American Journal of Bioethics, 21(2), 56-58.

Makoul, G. (2021). Patient-centered innovation: Lessons learned. Patient Education and Counseling, 104, 677-678.

Sharp, S. et al. (2016). The vital blend of clinical competence and compassion: How patients experience patient-centered care. Contemporary Nurse, 52(2-3), 300-312. DOI: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1020981

Solomon, D. & Robers, L. (2020, November 13). Centering racial equity in a new administration.