Kris English, PhD

Professor Emeritus of Audiology

University of Akron

Scene: Audiology Clinic

New Patient: My main concern about hearing aids is what people will think when they see them. I dread that kind of negative attention.

Audiologist: I understand why that would worry you.

New Patient: You do? Why? Are most people embarrassed about hearing aids?

And suddenly, the conversation has been derailed. While attempting to convey empathy, the audiologist inadvertently distracted the patient from her main concern – even though the “I understand” comment, on the surface, seemed patient-centered. What went wrong?

And suddenly, the conversation has been derailed. While attempting to convey empathy, the audiologist inadvertently distracted the patient from her main concern – even though the “I understand” comment, on the surface, seemed patient-centered. What went wrong?

From a counseling perspective, the audiologist’s response could be considered an unintended empathy disruption. In more blunt terms, sociologist Charles Derber (2000) would describe it as “conversational narcissism.” As an expert in everyday conversations, he provides a simple way to understand how our responses either shift or support the topic at hand.

Shift or Support?

Our example above is a shift–response, because it redirects the conversational focus to the audiologist, even though it was not intended to do so. In a clinical encounter, a shift-response temporarily interrupts the “empathy moment” by inserting the clinician’s presumptions of understanding, rather than keeping attention fully focused on the patient.

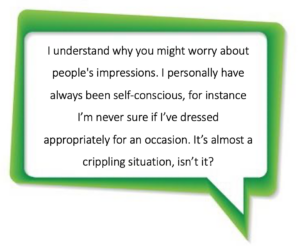

A shift-response can even unintentionally redirect the conversation altogether. For example, consider this purposely exaggerated response:

Of course, we would not let ourselves get carried away like this, but as we see in the opening scenario, even one sentence can inadvertently inject us into the patient’s narrative.

On the other hand, a support–response’s only goal is to acknowledge the other person’s comments. If the audiologist provided a support-response such as, “Could you tell me more about your concerns?” the empathic focus would have remained fully on the patient.

Worth Evaluating

How we strive to communicate empathy is important. When we say:

- I know how you feel…

- I understand why this is worrying you…

- I can see how this is difficult…

… we are effectively saying “This is me empathizing with you” and although it appears to be selfless, for a brief moment we are shifting attention to ourselves. Our ongoing goal, then: support, not shift or interrupt empathy.

There is No “I” in “Empathy”

| Sample Shift-Responses | Sample Support-Responses |

| I know how you feel. | How are you feeling about the situation? |

| I understand why this is worrying you. | This is weighing on your mind? |

| I can see how this is difficult. | This is a difficult stage for you. |

Note that the examples above are efforts to respond to a patient’s emotional state or “feeling mind” (Goleman, 2006). In comparison, when patients ask for help with technical issues such as changing hearing aid settings or using the phone (using their “thinking mind”), our “I” responses (“I understand what you are saying” or “I see what you are getting at”) do not derail the conversation but instead, represent an effort to co-construct understanding at the “thinking mind” level.

Conclusion

Consistent with support-responses, Josselman (1996) wrote that to be empathic, we must “put aside our own experience, at least momentarily” (p. 203) – a professional way of saying that, for the moment, “It’s not about us.”

References

Derber, C. (2000). The power of attention: Power and ego in everyday life (2nd ed.). NY: Oxford University Press.

Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ (2nd ed). New York: Bantam Books.

Josselman, R. (1996). The space between us: Exploring the dimensions of human relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.