Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

Professor Emeritus, Audiology

University of Akron

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd’s murder was captured on video and transmitted around the world, instantly sparking horror, outrage and grief while reigniting the Black Lives Matter movement in the US. During the same time period and since, a wealth of literature and research has been published describing the relationship of provider bias to inequitable healthcare, stimulating difficult and necessary self-examination, discussion and reflection.1-16

Five years later, it is deeply tempting to believe that bias and prejudice are no longer an issue, and that we can move on…

‘More than brick and mortar:’ DC begins removing ‘Black Lives Matter’ plaza

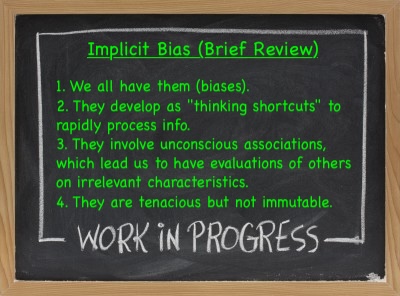

… but one thing we have learned: understanding and managing our many biases is a lifelong endeavor, especially re: our goal of person-centered counseling. To that end, a refresher course:

From “Think Cultural Health Education”

The table below presents steps we can take to confront our implicit biases and reduce stereotypic thinking. Consistent and conscious use of these strategies can help us create a habit of nonbiased thinking.

| STRATEGY | DESCRIPTION |

| Stereotype replacement | Become aware of the stereotypes you hold and create non-stereotypical alternatives to them |

| Counter-stereotypic imaging | Remember or imagine someone from a stereotyped group who does not fit the stereotype |

| Individuating | See each person as an individual, not a group member; pay attention to things about them besides the stereotypes of their group |

| Perspective-taking | Imagine the perspective of someone from a group different than your own (“Put yourself in the other person’s shoes.”) |

| Contact | Seek opportunities to engage in discussions in safe environments, spend time with people outside your usual social groups, or volunteer in a community different than your own. |

| Emotional regulation | Reflect on your “gut feelings” and negative reactions to people from different social groups. Be aware that positive emotions during a clinical encounter make stereotyping less likely. |

| Mindfulness | Keep your attention on the present moment so you can recognize a stereotypic thought before you act on it |

Leaning Into Necessary Work

As neuroscientists like to say, “If you have a brain, you have biases.”

It is painfully ironic how our growing brains blithely accepted biases as truths, and how challenging it can be to “unlearn” them. And yet, of course, every small “unlearning” is important: “It does not matter how slowly you go, so long as you do not stop.” —Confucius.

It is painfully ironic how our growing brains blithely accepted biases as truths, and how challenging it can be to “unlearn” them. And yet, of course, every small “unlearning” is important: “It does not matter how slowly you go, so long as you do not stop.” —Confucius.

Rest in peace, Mr. Floyd.

References

- Shen, M., et al. (2018). The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(1), 117-140. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

- Maina, I.W., et al. (2018) A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science in Medicine, 199, 219-22. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

- Chu, J., et al. (2019). The effect of patient-centered communication and racial concordant care on care satisfaction among U.S. immigrants. Medical Care Research and Review. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/1077558719890988

- Lipsitz, G. (2019). Sounds of silence: How race neutrality preserves white supremacy. In Crenshaw, K. et al. (Eds.), Seeing race again: Countering colorblindness across the disciplines(pp. 23-51). Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- FitzGerald, C., et al (2019). Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 7(1),29.

- Orgin R., et al. (2020). The inter-relationship of diversity principles for the enhanced participation of older people in their care: A qualitative study. International Journal of Equity in Health, 19:16.

- Balik C., et al. (2020). A systematic review of the discrimination against sexual and gender minority in health care settings.International Journal of Health Services, 50(1), 44-61.

- Joudeh, L. et al. (2021). “Little red flags”: Barriers to accessing health care as a sexual or gender minority individual in the rural southern United States—A qualitative intersectional approach. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 32(4), 467–480.

- Knoebel R. et al. (2021). Treatment disparities among the Black population and their influence on the equitable management of chronic pain. Health Equity, 5(1), 596-605.

- Forscher PS, et al. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522–559.

- Paul-Emile, K. (2017). Blackness as disability. LJ, 106, 293.

- Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., & Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual review of public health, 40(1), 105-125.

- Bazargan, M., Cobb, S., & Assari, S. (2021). Discrimination and medical mistrust in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of California adults.The Annals of Family Medicine, 19(1), 4-15.

- Hagiwara, N., Kron, F. W., Scerbo, M. W., & Watson, G. S. (2020). A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks.The Lancet, 395(10234), 1457-1460.

- Meints, S. M., Cortes, A., Morais, C. A., & Edwards, R. R. (2019). Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Management, 9(3), 317-334.

- Meidert, U., Dönnges, G., Bucher, T., Wieber, F., & Gerber-Grote, A. (2023). Unconscious bias among health professionals: a scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(16), 6569

Upskilling to an Essential Standard of Care

Upskilling to an Essential Standard of Care Taking the last question first: active listening is not about listening per se, but about interactivity. (It has been suggested that the term “conversational listening” might be more meaningful.1) While attending to a patient’s narrative, active listeners also verbally respond – with paraphrases, questions, affirmations, requests for clarifications, call-backs to previous topics – to assure patients that they are being heard.2,3

Taking the last question first: active listening is not about listening per se, but about interactivity. (It has been suggested that the term “conversational listening” might be more meaningful.1) While attending to a patient’s narrative, active listeners also verbally respond – with paraphrases, questions, affirmations, requests for clarifications, call-backs to previous topics – to assure patients that they are being heard.2,3

Incongruence hinders our ability to communicate empathy and warm acceptance to persons associated with those biases, and efforts to do so come across as inauthentic.

Incongruence hinders our ability to communicate empathy and warm acceptance to persons associated with those biases, and efforts to do so come across as inauthentic. It would not be unusual for helping professionals to miss the impact of unconscious / implicit bias on congruence – even Carl Rogers seemed to have overlooked it until rather late in his career. Crisp8 recently reported on two video recordings of Rogers’ therapy sessions with two different Black male patients, conducted 5 years apart. The first session from 1979 was described by peers as having a “therapist-centric perspective” (p. 223) with missed opportunities to respond with empathy to the client’s racism experiences and avoiding an exploration about their racial and cultural differences.

It would not be unusual for helping professionals to miss the impact of unconscious / implicit bias on congruence – even Carl Rogers seemed to have overlooked it until rather late in his career. Crisp8 recently reported on two video recordings of Rogers’ therapy sessions with two different Black male patients, conducted 5 years apart. The first session from 1979 was described by peers as having a “therapist-centric perspective” (p. 223) with missed opportunities to respond with empathy to the client’s racism experiences and avoiding an exploration about their racial and cultural differences.

Recently, an additional consideration of patients in the LGBTQ community receiving care in these settings indicated comparably positive PDQ results,12 but also raises a question: why wait until the end stage of healthcare? Social dignity violations (e.g., dismissal, disregard, grouping) routinely occur across a wide range of healthcare encounters throughout a lifetime.13-18 There seems no reason to wait: researchers very familiar with the PDQ have pointed out that the PDQ “can be used by any provider type and in numerous care settings to understand patient values” as a standard of care.19 Since all patients seek relational dignity throughout their lives, extending the PDQ intervention to all patients in all settings seems feasible, or at the minimum to those with historical concerns regarding inequitable care.

Recently, an additional consideration of patients in the LGBTQ community receiving care in these settings indicated comparably positive PDQ results,12 but also raises a question: why wait until the end stage of healthcare? Social dignity violations (e.g., dismissal, disregard, grouping) routinely occur across a wide range of healthcare encounters throughout a lifetime.13-18 There seems no reason to wait: researchers very familiar with the PDQ have pointed out that the PDQ “can be used by any provider type and in numerous care settings to understand patient values” as a standard of care.19 Since all patients seek relational dignity throughout their lives, extending the PDQ intervention to all patients in all settings seems feasible, or at the minimum to those with historical concerns regarding inequitable care.

possesses” (1986, p. 391). More simply, “The factors that influence behavior are embedded in the belief that one has the capability to accomplish that behavior” (Klassen & Klassen, 2018, p. 76).

possesses” (1986, p. 391). More simply, “The factors that influence behavior are embedded in the belief that one has the capability to accomplish that behavior” (Klassen & Klassen, 2018, p. 76).