Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

The University of Akron/NOAC

Audiologic counseling is like a two-sided coin: one side attends to patients’ emotional and psychological struggles, and the other side, to their need for clear, relevant, and compelling information. Goleman (1995) would describe these two goals as communicating either with the “feeling mind” or the “thinking mind.” The concept of “being of two minds” is a familiar one, but communicating with a patient’s “thinking mind” (more specifically, our efforts in patient education) hasn’t attracted much attention in audiology.

Patient education can be taken for granted, but that would be a grave mistake. If not careful, we might apply a range of ineffective practices, such as:

- Using words our patients can’t process;

- Providing more detail than patients can remember;

- Conveying information unrelated to patients’ questions;

- Providing information without helping patients apply it to their lives.

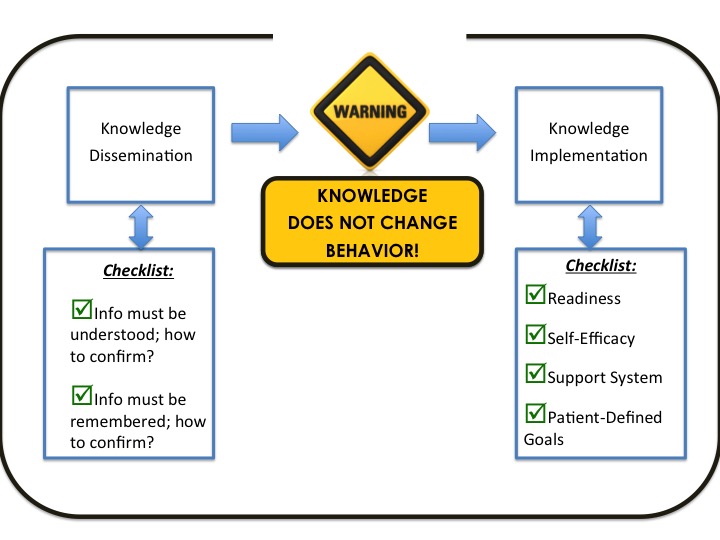

Let’s ponder that last point for a moment. Information designed to “help patients apply it to their lives” elevates patient education to a new level of responsibility. We are not only talking about providing information, but also using information as a vehicle for change.

This concept is relatively new. Falvo (2011) notes that while “many people think of patient education as the transfer of information … the real goal is patient learning, in which patients are not only provided with information, but helped to incorporate it into their daily lives” (p. 21). We are being invited to redefine this process, to evolve from a monologue of information-giving into an interactive framework for change.

The concept of “effective patient education” can be new territory for many audiologists. How do we find our way? This article outlines a suggested checklist to guide us, applying classic teaching/learning principles culled from exemplar patient education materials.

A Checklist for Audiology

Patient education has a familiar starting point: knowledge dissemination.

Knowledge Dissemination. We have much information to share about test results, anatomy, etiologies, genetics, recommendations, treatments. However, as part of effective patient education, this step is just the first of several considerations. Even as we disseminate information, we cannot assume the patient understands us, or will remember what we said accurately. Let’s consult this checklist of concerns:

As we disseminate knowledge:

Does our patient understand us? In addition to the problems with professional jargon, we must remember that when a patient is upset, the amgydala in the brain activates “flight or fight” responses (increased heart and respiration rates, etc.). While in this state, the frontal cortex (the center for analysis and reasoning) is inaccessible. We might be talking to a brain that, for the time being, cannot learn. How to test for understanding? The easiest way is to ask: “Would you like a detailed explanation, or a big-picture summary? Do you prefer information conveyed verbally, or in writing, or both?” And later, “To be sure we are on the same page: could you share with me your understanding of the situation?” Asking the patient to repeat what they understand is called the “teach-back method” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Continue reading

Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

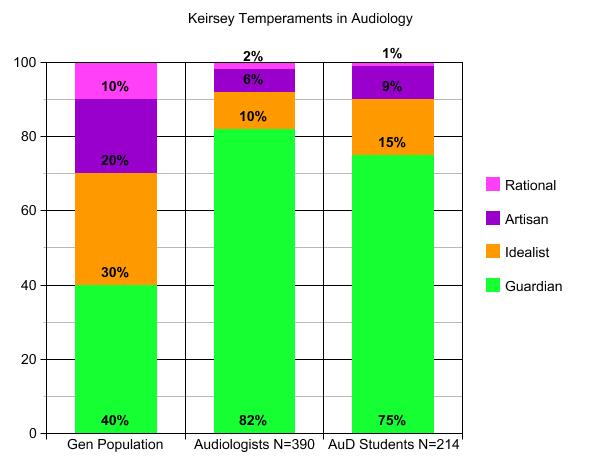

Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to

Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to  Kara Vasil, Class of 2016

Kara Vasil, Class of 2016 Two Things Click

Two Things Click

Laura Rickey, Class of 2017

Laura Rickey, Class of 2017

Soon I learned she has a busy social life and takes part in many activities, but having the hearing loss had started to affect all this. This patient has been coming to our clinic for over a year and had never had the chance to really speak about how the hearing loss was affecting her.

Soon I learned she has a busy social life and takes part in many activities, but having the hearing loss had started to affect all this. This patient has been coming to our clinic for over a year and had never had the chance to really speak about how the hearing loss was affecting her.

Devon Weist, AuD

Devon Weist, AuD

Peter Huchinson, Class of 2016

Peter Huchinson, Class of 2016 Providing patient-centered care is something that sounds appealing and makes logical sense, but often I find difficult to practice. When I see a moderate, sloping, high frequency hearing loss, I think about the hearing aid I will recommend at the end of the appointment. When a patient complains of dizziness upon getting out of bed, I consider BPPV. These initial thoughts are natural, and there is nothing wrong to start thinking about the issue at hand and the recommendation that I will make. The problem is that I often find myself stopping there. I forget to consider the needs and desires of that particular patient. I forget to consider the patient’s activity limitations, participation restrictions, and perceived or experienced stigma. I forget to consider the emotional journey that the patient has been on for much longer than the last 30 minutes that they have been in my sound booth.

Providing patient-centered care is something that sounds appealing and makes logical sense, but often I find difficult to practice. When I see a moderate, sloping, high frequency hearing loss, I think about the hearing aid I will recommend at the end of the appointment. When a patient complains of dizziness upon getting out of bed, I consider BPPV. These initial thoughts are natural, and there is nothing wrong to start thinking about the issue at hand and the recommendation that I will make. The problem is that I often find myself stopping there. I forget to consider the needs and desires of that particular patient. I forget to consider the patient’s activity limitations, participation restrictions, and perceived or experienced stigma. I forget to consider the emotional journey that the patient has been on for much longer than the last 30 minutes that they have been in my sound booth.