Karen Muñoz, EdD

Karen Muñoz, EdD

Utah State University

The importance of counseling is well recognized for the vital role it plays in audiology service delivery. There are text books devoted to counseling (e.g., Clark & English, 2014), and continuing education opportunities for interested professionals. Counseling is included in audiology scopes of practice (ASHA, 2004; AAA, 2004), and audiology preferred practice guidelines (ASHA, 2006). It sounds like as a profession we have this covered. But do we?

Even though there is agreement on the foundational role counseling plays in audiology service delivery, the lack of depth in professional practice guidelines leaves expectations for graduate training vague. Counseling competencies, just like other skills audiologists learn, need intentional instruction for knowledge and skill acquisition. Similar to student learning for other evidence-based audiology services, bridging of knowledge is needed between coursework and clinical experiences. For this to occur, clinical supervisors need to be intentionally practicing and teaching evidence-based counseling skills. Without careful attention to counseling training, it is unlikely that graduate students will be purposeful in their approach to counseling. You may be thinking, of course counseling is happening, why would this be a problem that needs attention?

Counseling Skills: Not a Given

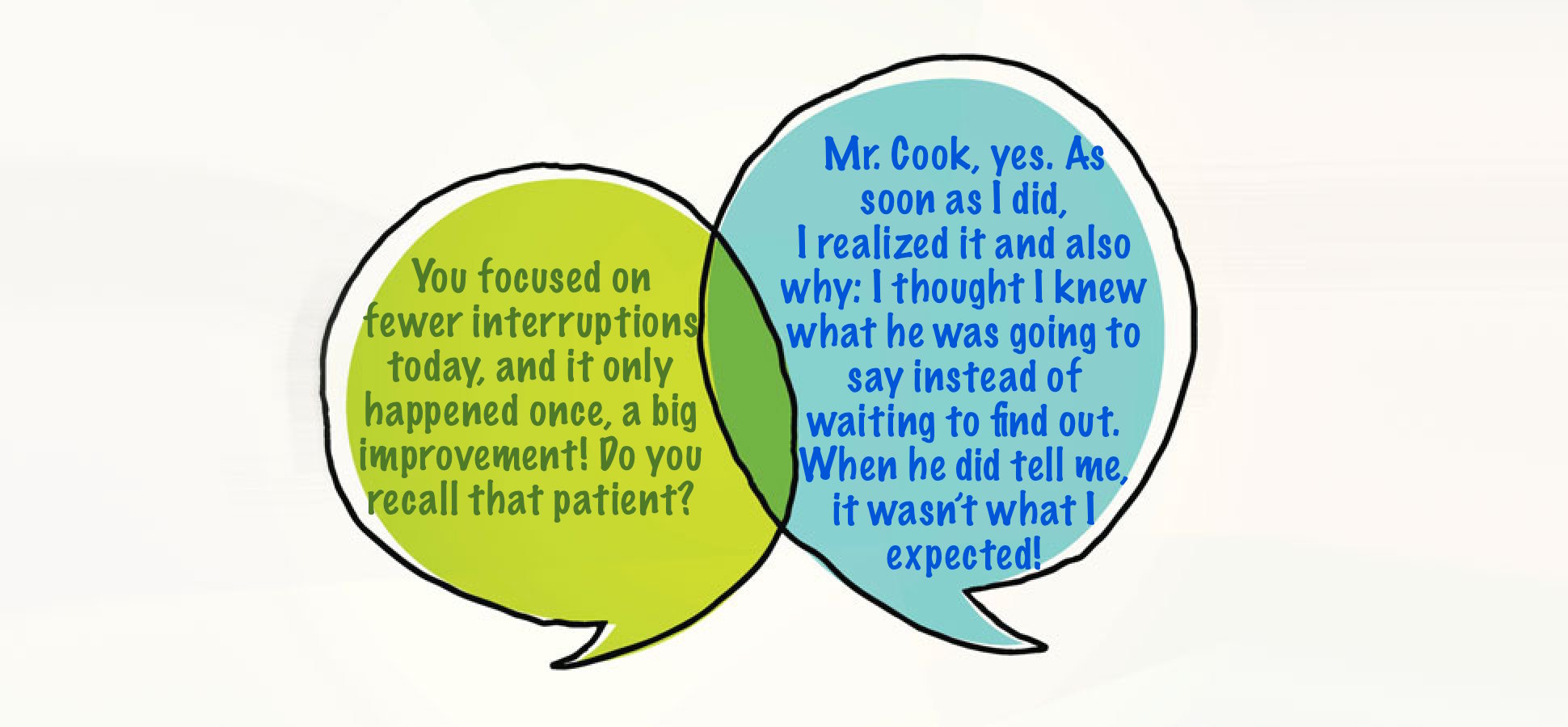

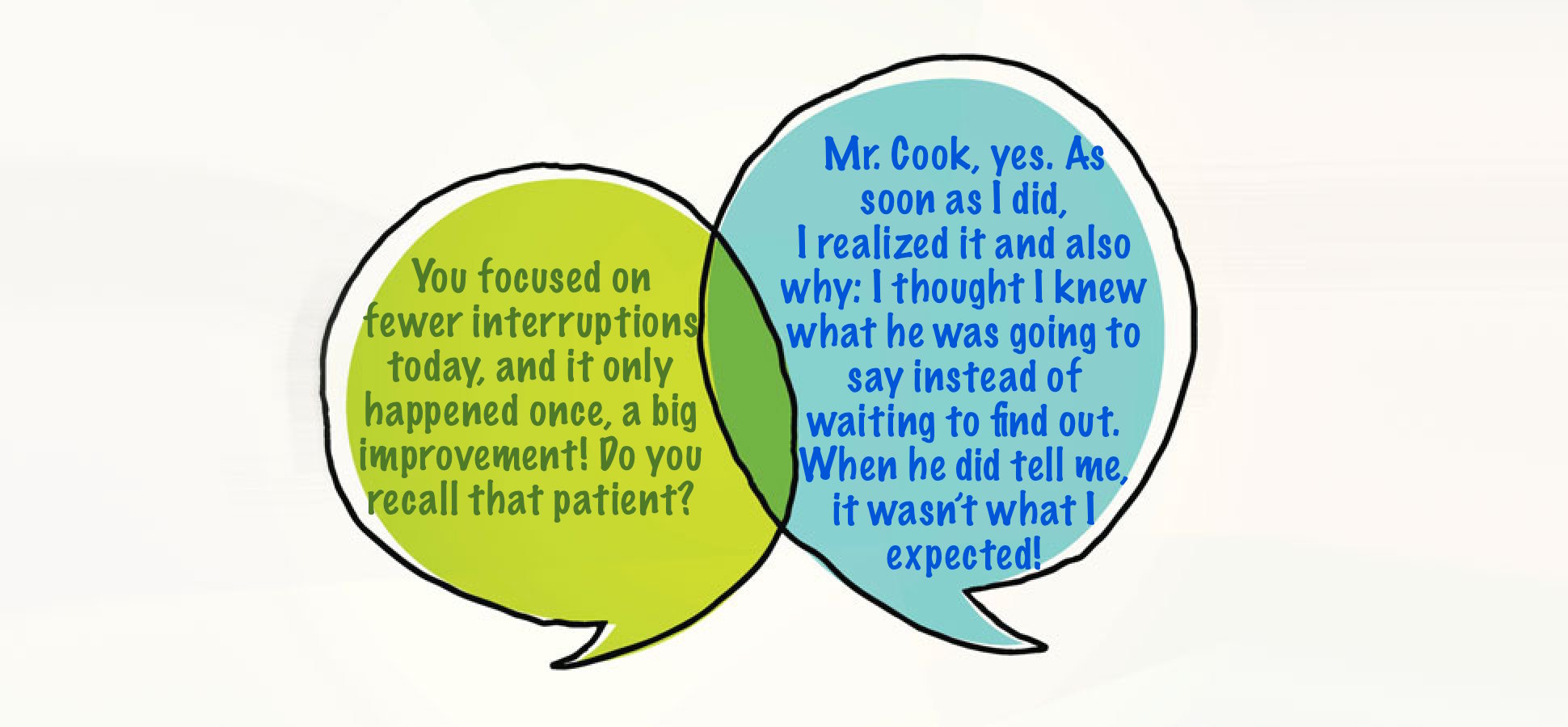

Patients have shared their experiences with audiologists and it is clear that counseling ability does not just happen to develop along the way. Parents have reported gaps in the information and support they received (e.g., Larsen et al., 2012; Muñoz et al. 2013). Hearing aid uptake among adults with hearing loss is low (Kochkin, 2009), but influential factors are not well defined. There is a need for further research to better understand the influence of factors such as audiologists’ counseling skills, patient self-efficacy, and overall type and quality of interactions between the audiologist and patient (Knudsen et al., 2010). Recent research has also raised concerns with how counseling conversations are happening in audiology. Analysis of audio-recorded appointments with adult clients considering hearing aids revealed that audiologists responded to client psychosocial concerns with technical information, ignoring the emotional content of concerns raised (Ekberg et al., 2014). During history-taking, in a related study, audiologists often interrupted the client early on, and then maintained verbal dominance during the appointment (Grenness et al., 2014).

Patient Centered Care

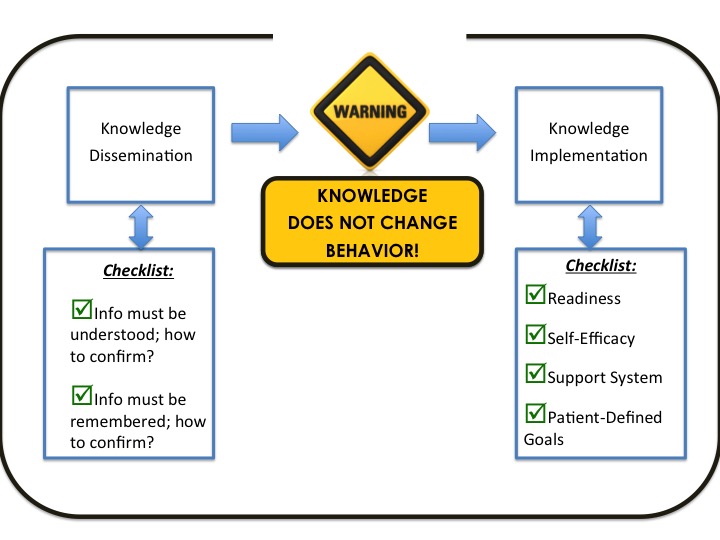

Patient-centered care is widely recognized as an important feature of healthcare delivery that can lead to improved outcomes and adherence with recommendations (Robinson et al., 2008; Zolnierek & DiMatteo, 2009). Patients seeking audiology services, not surprisingly, also want services that are patient-centered (Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2014). It may seem that being patient-centered should occur if the practitioner values it and is aware, but awareness alone is not sufficient for changing behavior (Muñoz et al., 2015). Counseling is more than being a caring and compassionate professional, and while the skills needed to provide effective counseling are not necessarily difficult to learn, they are not intuitively implemented. Just think about a time when you did not feel heard, or were not given an opportunity to voice your thoughts, or were told how to fix your health concern.

Focus and Feedback

Effective use of counseling skills requires knowledge about behavior and factors that influence behavior (yours and your patients), opportunity to practice implementing skills, and performance feedback. In other words, it needs to be intentionally taught, just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes.

just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes.

References

American Academy of Audiology. (2004). Scope of practice.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2004). Scope of practice in audiology.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2006). Preferred practice patterns for the profession of audiology.

Ekberg K, Grenness C, & Hickson L. (2014) Addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. American Journal of Audiolology, 23, 337-350. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0011

Clark, J.G., & English, K.M. (2014). Counseling-infused audiologic care.Boston: Pearson.

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A., Meyer, C., & Davidson, B. (2014). Communication patterns in audiologic rehabilitation history-taking: Audiologists, patients, and their companions. Ear & Hearing, 36, 191-204.

Knudsen, L.V., Oberg, M., Nielsen, C., Naylor, G., & Kramer, S.E. (2010). Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: A review of the literature. Trends in Hearing, 14(3), 127-154.

Kochkin, S. (2009). MarkTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market.

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Grenness, C. (2014). An Australian survey of audiologists’ preferences for patient-centeredness. International Journal of Audiology, 53:sup1, S76-S82.

Larsen, B., Muñoz, K., DesGeorges, J., Nelson, L., & Kennedy, S. (2012). Early Hearing Detection and Intervention: Parent experiences with the diagnostic hearing assessment. American Journal of Audiology, 21, 91-99.

Muñoz, K., Blaiser, K., & Barwick, K. (2013). Parent hearing aid experiences in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(1), 5-16.

Muñoz, K., Nelson, L., Blaiser, K, Price, T., & Twohig, M. (2015). Improving support for parents of children with hearing loss: Provider training on use of targeted communication strategies. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26(2), 116-127.

Robinson, J.H., Callister, L.C., Berry, J.A., & Dearing, K.A. (2008). Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. Journal of American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 600-607.

Zolnierek, K.B.H., & DiMatteo, M.R. (2009). Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care, 47(8), 826-834. Doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue?

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue? Question #2 Why do patients break eye contact? What does it mean when a patient looks away from our face, or withdraws from our joint attention on devices or forms? We can’t be sure, but the patient is probably thinking about/feeling something new. Perhaps he is trying to process what we are saying. Perhaps a wave of emotion has interrupted his ability to concentrate. Perhaps our conversation triggered a memory, a doubt, a worry, a question, a regret, a recognition of embarrassing-but-real vanity (Kajimura & Nomura, 2016).

Question #2 Why do patients break eye contact? What does it mean when a patient looks away from our face, or withdraws from our joint attention on devices or forms? We can’t be sure, but the patient is probably thinking about/feeling something new. Perhaps he is trying to process what we are saying. Perhaps a wave of emotion has interrupted his ability to concentrate. Perhaps our conversation triggered a memory, a doubt, a worry, a question, a regret, a recognition of embarrassing-but-real vanity (Kajimura & Nomura, 2016).

John Greer Clark, PhD

John Greer Clark, PhD professions in many ways. I am sure that we are not unique in the dilemma that classroom teaching does not always reflect what students practice in their clinical settings. In the 1960s and 1970s we ardently argued that the full management of hearing loss, including the dispensing of products to assist those with hearing deficits, could indeed be done ethically. And we argued that we were the best prepared to provide this service and that we could do it better. I do believe we are better prepared and can fully service those with hearing loss more effectively than other hearing health care professions. However, it is dismaying that we largely adopted the dispensing practices already in place and have not substantially deviated from these over the years to incorporate better use of personal adjustment counseling and to address more fully the rehabilitative needs of patients.

professions in many ways. I am sure that we are not unique in the dilemma that classroom teaching does not always reflect what students practice in their clinical settings. In the 1960s and 1970s we ardently argued that the full management of hearing loss, including the dispensing of products to assist those with hearing deficits, could indeed be done ethically. And we argued that we were the best prepared to provide this service and that we could do it better. I do believe we are better prepared and can fully service those with hearing loss more effectively than other hearing health care professions. However, it is dismaying that we largely adopted the dispensing practices already in place and have not substantially deviated from these over the years to incorporate better use of personal adjustment counseling and to address more fully the rehabilitative needs of patients. Every Patient’s Story Matters

Every Patient’s Story Matters Karen Muñoz, EdD

Karen Muñoz, EdD

just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes.

just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes. Judith Blumsack, PhD

Judith Blumsack, PhD

There was no terminology for my approach at the time, but now I know it can be called audiologist-centered (i.e., it was all about me). Consistent with my quiz answers, I expected to direct the appointment, while the patient passively followed my lead. I didn’t intend to be disrespectful or dismissive of the patient’s role, but I held a naïve (some would say paternalistic) assumption that patients had no say because they didn’t know what I knew, and I knew best. In reality, of course adult patients are anything but passive: they are autonomous beings and they will make decisions with or without our involvement (Tauber, 2005).

There was no terminology for my approach at the time, but now I know it can be called audiologist-centered (i.e., it was all about me). Consistent with my quiz answers, I expected to direct the appointment, while the patient passively followed my lead. I didn’t intend to be disrespectful or dismissive of the patient’s role, but I held a naïve (some would say paternalistic) assumption that patients had no say because they didn’t know what I knew, and I knew best. In reality, of course adult patients are anything but passive: they are autonomous beings and they will make decisions with or without our involvement (Tauber, 2005).

When we examine this “auto-pilot” practice, even more questions emerge. What would happen if we do give patients a choice, and ask if they would prefer a “big picture” summary or the details? If they choose “big picture summary,” will we freeze up? Do we use the audiogram as a prop, or can we put our test results to one side, use simple terms to clearly relate the findings to their initial concerns, and move on?

When we examine this “auto-pilot” practice, even more questions emerge. What would happen if we do give patients a choice, and ask if they would prefer a “big picture” summary or the details? If they choose “big picture summary,” will we freeze up? Do we use the audiogram as a prop, or can we put our test results to one side, use simple terms to clearly relate the findings to their initial concerns, and move on?

Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

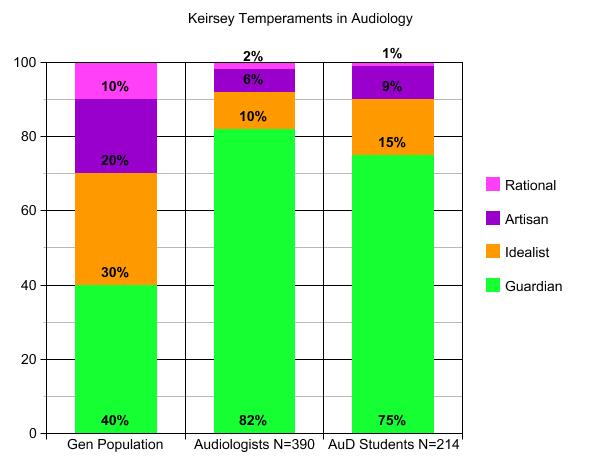

Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to

Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to