Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

Giri Sundar, MPhil/PhD

Osborne College of Audiology Director, Distance Education

Salus University

As a clinical audiologist for over 25 years, I have encountered numerous people with hearing loss, only to conclude that this is not a homogeneous group. What differentiates each patient is his or her unique story; fortunately for us, if we allow the story to unfold, we will learn how to help. Here is an example:

One of my patients described a get-together in the family. He has three children and five grandchildren. They had all arrived from different parts of the northeast, and he had not seen them together in some time. Once the entire clan was in the dining room, everything (chairs, cutlery, plates, people, mouths) was in constant motion. The dining table was the only thing that did not move.

My patient’s eyes could not quite keep up with the pace of activity; dependent on the visible word, his social encounters were manageable when limited to roomful of one or two people, and he’d developed his own strategies to cope with his hearing loss in simple listening conditions. But too many people in one room with the scattered sources of sounds left him unnerved.

Sounds blended together in a din and he retreated into the sanctuary of his study, leaving his dinner unfinished. He could not tolerate the blurring of words; he could not participate or even spectate. The very people he loved seemed insufferable and tiresome. His retreat, however, was misconstrued by his grown children and created quite a bit of tension in the following days. His wife’s observation of the possibility of hearing loss being at the root of this behavior allowed the rest of the family member to somewhat understand this gentleman, and upon his daughter’s insistence he decided to seek some help.

He was quite forthright when I asked him what made him see an audiologist at this particular time. Although in the beginning he only wanted a hearing test, routine questions regarding his communication difficulties brought his real story: he felt an alienation from his family.

He often had to imagine what they might be saying. “No one wants to listen or take the time to listen. Going out with people you comfortably socialized with has become something of an ordeal…it is claustrophobic; when you are in the middle of a group of people and cannot participate in the conversation, it is as though the people around you suffocate you. You know what I mean?”

I asked him if he wanted hearing aids. He did not: he only wanted to know if he had bad hearing loss. The answer told me my patient did not yet realize himself that the issue was his hearing problem (unique to him and his life), not his hearing loss. Because I understood his story, I could help him make the connection between his hearing loss and the alienation that had been hurting him so much.

Kris English, PhD

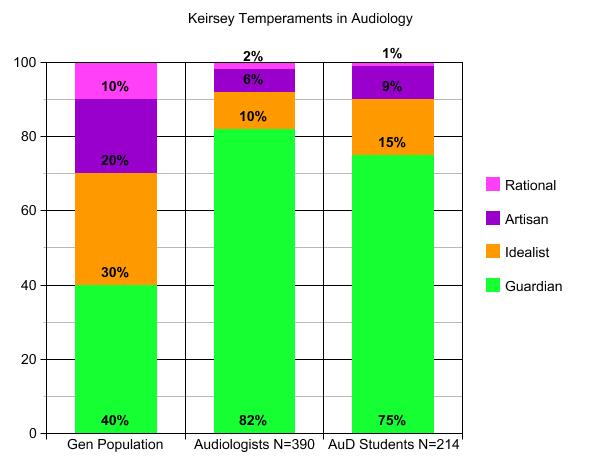

Kris English, PhD Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to

Ten years and 25 semesters later, with results from 390 audiologists (all with MA degrees and an average of 15 years experience), the summative data show a very strong tendency toward Guardian temperaments (82% in the middle bar, compared to 40% in the general population on the left). Since then, I have posed the same assignment to AuD graduate students (another 10-year project from 2008 to 2018, right hand bar), and have also frequently asked attendees at workshops to

Devon Weist, AuD

Devon Weist, AuD

John Greer Clark, PhD

John Greer Clark, PhD But not all patients who come through our doors have reconciled themselves with their hearing loss. Some still harbor varying degrees of denial, continuing to place much of the blame for communication failures on the speaking habits of others. And these others continue to be viewed as residing in the enemy camp, pushing for actions that are not wanted or that are not perceived as needed.

But not all patients who come through our doors have reconciled themselves with their hearing loss. Some still harbor varying degrees of denial, continuing to place much of the blame for communication failures on the speaking habits of others. And these others continue to be viewed as residing in the enemy camp, pushing for actions that are not wanted or that are not perceived as needed.