Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

The University of Akron/NOAC

This entry concludes a discussion on Patient-Centered Care with several applications to audiology practices. The first four entries are:

As mentioned in Part 4, finding common ground is often assumed to be our final step, since we’ve agreed on next steps and are ready to conclude the appointment. But the difference between a transaction and patient-centered care includes one more component: our skill in enhancing patient relationships.

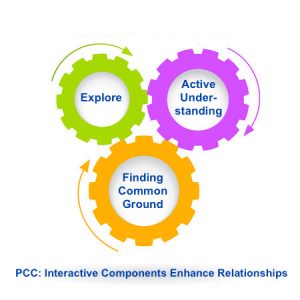

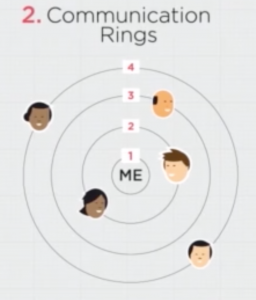

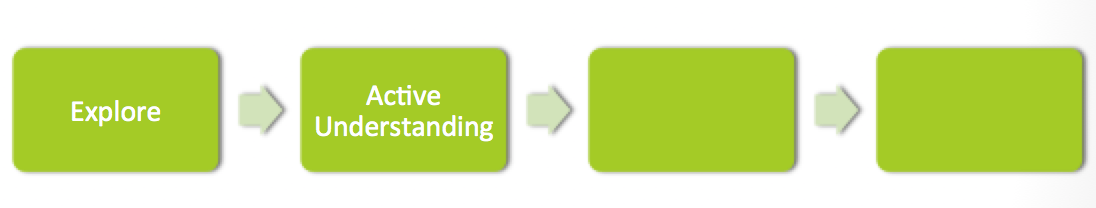

Stewart et al. (2014) described these four components as interactive, and here is where we see it most clearly: forward-moving steps to an ultimate goal. We don’t explore for exploring’s sake, but to understand (and actively indicate that we understand) our patient’s needs as prerequisites to finding common ground.

However, the linearity of this model doesn’t do justice to the interactive impact of each component. Perhaps we can envision a set of cogs, each one vital to the process and each one affecting the others. Regardless, we are ready to consider some aspects of our last component:

Enhancing Patient Relationships

Stewart et al. (2014) list several characteristics associated with each interactive component of patient-centered care. Among those related to “Enhancing Patient Relationships,” we will focus on two that could be considered two sides of the same coin: empathy and self-awareness.

A piano sounding board

§ Empathy: Gallese et al. (2007) describe empathy as “intentional attunement” to another person’s experience, bringing to mind the metaphor of a sounding board. As clinicians dedicated to sound, we might especially “resonate” to Josselman’s (1996) definition: the ability to “put aside our own experience, at least momentarily, and reverberate to the feelings of another” (p. 203).

Interestingly, recent fMRI studies confirm that humans do in fact need to “put aside” other thinking as we empathize. Jack et al.’s 2013 report on fMRI studies indicate that humans seem to have a built-in neural constraint that prevents us from thinking empathically and analytically at the same time. The need to “toggle” from one mental state to another requires mindfulness, i.e. “a constant awareness of the encounter at multiple levels” (Scott et al., 2008, p. 319). We don’t give ourselves enough credit when we say “All I did was listen” – since “just listening” means an intentional decision about where we direct our attention.

§ Self-awareness: Epstein (1999) identified five types of self-awareness:

- Intrapersonal awareness of our own strengths and limitations

- Interpersonal awareness of how we are seen by others

- Learning awareness of our knowledge and skill levels, and the means to achieve learning goals

- Ethical awareness of our values and how they shape treatment decisions

- Technical awareness of our need to correct procedures in process, including communication

Readers will likely agree that, except for ethics, these types of self-awareness are not discussed much in audiology. However, it has been observed time and again, including by McWhinney (1989), that “We cannot begin to know others until we know ourselves” (p. 82).

Intrapersonal awareness would include knowing our strengths as helpers, dedicated to hearing and balance health. If we are consistent with the general population, we are probably extroverts, but about one-fourth of us, as introverts, may not be fully aware of experiencing a greater energy drain from daily patient care compared to our extroverted colleagues. Our energy levels can affect patient care, but the toll is rarely acknowledged (although colleagues half-jokingly suggest a support group for “Introverted Auds” — as long as it doesn’t involve meeting and talking).

It seems we may not be like the general population when it comes to temperament. Informal data suggest we are twice as likely to be Guardians as classified by the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, which provides food for thought when we consider typical characteristics. Might Guardians sometimes struggle with patient-centeredness? An AuD student recently gave himself the opportunity to transcend this tendency.

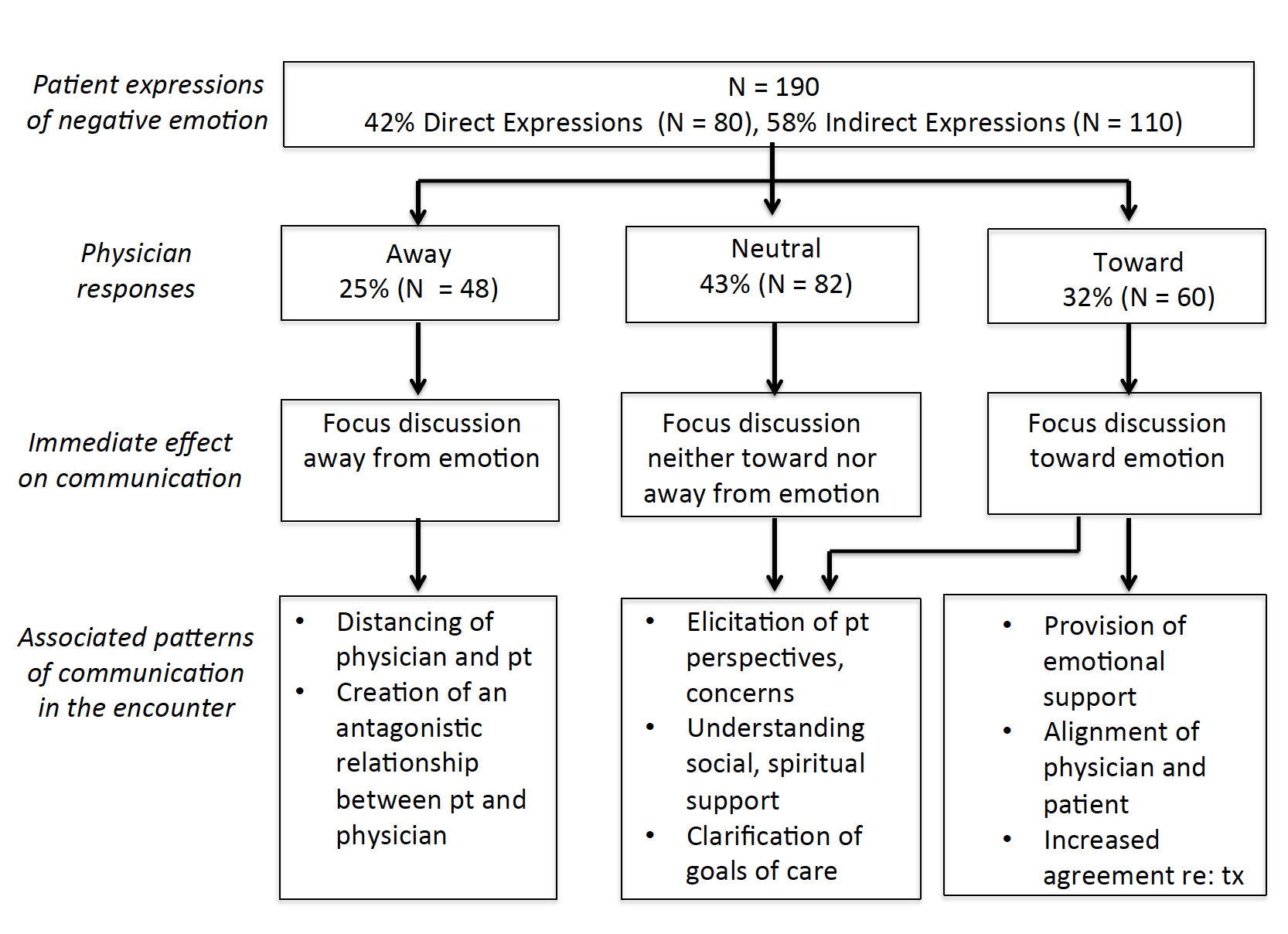

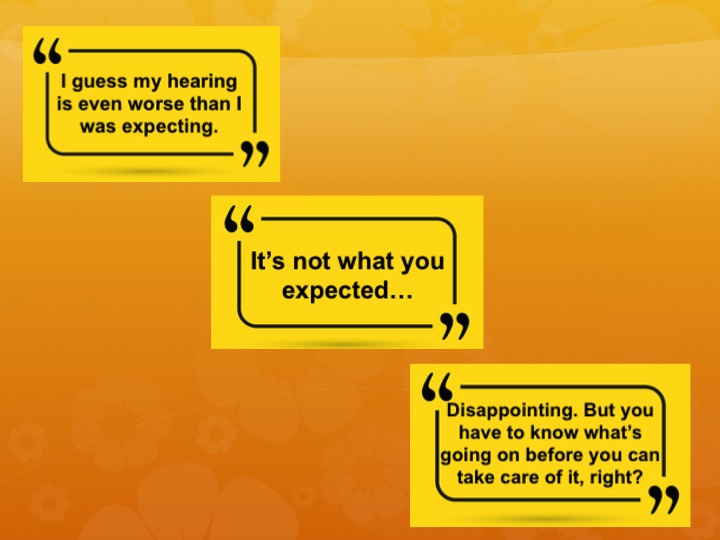

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

“A female patient felt her old hearing aids needed replacing. She had had three sets over the past 13 years. At today’s appointment, she posed many questions about her audiogram, wanting a ‘thorough explanation’ of her long-standing HL.”

Here is where the audiologist stepped “into the breach.” He did not have to ask any follow-up questions, but he did: “When I asked her how she was feeling, she got very emotional and left the room to compose herself. When she returned, she explained that she now realized for the first time that her hearing loss was not going to get better.”

Was this conversation uncomfortable for the audiologist? Yes — but he approached it anyway. What it therapeutic for the patient? She indicated it was: she felt grief but also relief, after all those years of holding on to false hope. We will find ourselves occasionally challenged to decide between our discomfort and potential patient catharsis and clarity. Those who are comfortable with difficult conversations could serve as mentors to those who are not. Avoidance helps no one, and is the antithesis of patient-centeredness.

Enhancing Relationship Tip #1: Empathy is Teachable

If empathy is not an innate skill, or was not nurtured (or even crushed!) in graduate school, clinicians can still evolve as empathizers, especially with self-evaluations or feedback from colleagues. Lundeby et al. (2015) provide a “teachable consultation model” that could serve as a study-group project with like-minded audiologists. (Contact the author [[email protected]] to request a copy.)

Enhancing Relationship Tip #2: Know Your Temperament

Are you a Guardian like most audiologists? Or an Artisan, Realist, Idealist? And how does your temperament align with your clinical goals? Find out at the Keirsey Temperament website. (Tip #3: after setting up an account, answer 71 questions; your results will follow in a Mini Report. Paying for additional information is not necessary!)

The Ultimate Question: Are “Enhancing Patient Relationships” an Evidence-Based Practice?

In addition to research and our own clinical expertise, EBP also considers patient values. For one patient’s (and her readers’) perspective, see “Are Audiologists from Mars?” We must ask ourselves: if she had enhanced relationships with her audiologists, would she need to create a wish list?

And finally, some food for thought: ever wondered about the consequences of putting other priorities ahead of patient-centered care? Consider this essay.

1. I am aware of the attention required to toggle between empathy and problem-solving.

Yes Working on it Not sure what this means

2. I can explain how a “Guardian” temperament might be at odds with patient-centered practices.

Yes I haven’t given this much thought

3. I am generally comfortable engaging with difficult conversations in clinical settings.

Yes Working on it Would rather avoid them

4. I can explain how all four components to patient-centered care interact with each other.

Yes Working on it Not sure what this means

References

English, K., Jennings, M.B, Lind, C., Montano, J., Preminger, J., Saunders, G., Singh, G., & Thompson, E. (2016). Family-centered audiology care: Working with difficult conversations. Hearing Review, 23(6), 14-17.

Epstein, R. (1999). Mindful practice. JAMA, 282(9), 833-839.

Gallese, V., Eagle, M., & Migone, P. (2007). Intentional attunement: Mirror neurons and the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relationships. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55(1), 131-175.

Jack, A., et. (2013). fMRI reveals reciprocal inhibition between social and physical cognitive domains. NeuroImage, 66, 385-401.

Josselman, R. (1996). The space between us: Exploring the dimensions of human relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lundeby, T. Gulbrandsen, P., & Finset, A. (2015). The expanded Four Habits Model: A teachable consultation model for encounters with patient in emotional distress. Patient Education and Counseling, 98, 598-603.

McWhinney, I. (1989). A textbook of family medicine. NY: Oxford University Press.

Scott, J., et al. (2008). Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine, 6(4), 315-322.

Stewart, M., Brown, J.B., Weston, W.W., McWhinney, I.R., McWilliams, C.L., & Freeman, T.R. (2014). Patient centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method (3rd ed.). London: Radcliff Publishing.

Diana Harbor, BA

Diana Harbor, BA Yesterday I had the privilege of being with a group of teenagers all living with hearing loss, using different technology from cochlear implants to bone implanted devices with different personalities and experiences of the world, some who had never met each other before. We all took part in an exciting improv, drama workshop at the Ear Foundation. Much of the afternoon was spent in small groups creating wonderful stories and weaving a single idea into a feast of creativity that JK Rowlings would have drooled at. And the real magic happened as Loydie, a DJ from Capital radio, revealed to us very simple techniques for keeping ideas going, for turning problems into new ideas and for getting the best out of each other. The power of using the phrase “…yes and” and how to do this while listening and maintaining eye contact.

Yesterday I had the privilege of being with a group of teenagers all living with hearing loss, using different technology from cochlear implants to bone implanted devices with different personalities and experiences of the world, some who had never met each other before. We all took part in an exciting improv, drama workshop at the Ear Foundation. Much of the afternoon was spent in small groups creating wonderful stories and weaving a single idea into a feast of creativity that JK Rowlings would have drooled at. And the real magic happened as Loydie, a DJ from Capital radio, revealed to us very simple techniques for keeping ideas going, for turning problems into new ideas and for getting the best out of each other. The power of using the phrase “…yes and” and how to do this while listening and maintaining eye contact.

Jeanine Doherty, Au.D., M.Phil., M.B.S, B.Soc.Sci.(Hons.),

Jeanine Doherty, Au.D., M.Phil., M.B.S, B.Soc.Sci.(Hons.),  As we know, ethics, legality and morality are each different, though related, constructs. Something can be legal, yet immoral to an individual, as our values lead to our personal morals. Moral distress arises when clinicians are unable to act according to their moral judgement and their Profession’s Ethical Code (Rodney, 2017). This distress is located not only within individuals when their actions mismatch their values, but also from within the broader healthcare structures of the clinician’s workplace. The socio-political structures that can create moral/ethical distress have been studied mostly within nursing, but the relevance of the concept to audiology should not be ignored. Moral distress also emerges from situations that are against all the principles of PCC.

As we know, ethics, legality and morality are each different, though related, constructs. Something can be legal, yet immoral to an individual, as our values lead to our personal morals. Moral distress arises when clinicians are unable to act according to their moral judgement and their Profession’s Ethical Code (Rodney, 2017). This distress is located not only within individuals when their actions mismatch their values, but also from within the broader healthcare structures of the clinician’s workplace. The socio-political structures that can create moral/ethical distress have been studied mostly within nursing, but the relevance of the concept to audiology should not be ignored. Moral distress also emerges from situations that are against all the principles of PCC. Harris and Griffin (2015) write that some organisational policies can lead to diminished care quality and cynicism with lack of teamwork and lower morale amongst clinical staff. In such a work-place, increased competition and mistrust develops between staff, while middle management level finds itself stuck between demands from higher-up levels (e.g. profit/cost outcomes) and the lack of teamwork and lower morale of the clinicians who are in moral distress. The physiological and psychological effects caused by the existence of moral distress can lead to burn-out, and then the staff member becomes ill, finds another better workplace, or just gives in, morally disengages, and carries on in a manner that is opposed to their values/morals (Musto, Rodney & Vanderheide, 2015). Lachman’s (2016) list of symptoms of burnout includes fatigue, general illness, headaches, insomnia, disillusionment, anger, negative self-concept and a loss of concern for others.

Harris and Griffin (2015) write that some organisational policies can lead to diminished care quality and cynicism with lack of teamwork and lower morale amongst clinical staff. In such a work-place, increased competition and mistrust develops between staff, while middle management level finds itself stuck between demands from higher-up levels (e.g. profit/cost outcomes) and the lack of teamwork and lower morale of the clinicians who are in moral distress. The physiological and psychological effects caused by the existence of moral distress can lead to burn-out, and then the staff member becomes ill, finds another better workplace, or just gives in, morally disengages, and carries on in a manner that is opposed to their values/morals (Musto, Rodney & Vanderheide, 2015). Lachman’s (2016) list of symptoms of burnout includes fatigue, general illness, headaches, insomnia, disillusionment, anger, negative self-concept and a loss of concern for others. Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

Moving Toward Common Ground

Moving Toward Common Ground

Please note: finding common ground means “mutually influencing each other, each potentially ending up in a place different from where they began, with different understandings than either would have reached alone. It is not a matter of who has power and who does not.” (Stewart et al., 2014, p. 138). (More on

Please note: finding common ground means “mutually influencing each other, each potentially ending up in a place different from where they began, with different understandings than either would have reached alone. It is not a matter of who has power and who does not.” (Stewart et al., 2014, p. 138). (More on

1. I can explain the difference between “informative” and “interpretive” models in patient care.

1. I can explain the difference between “informative” and “interpretive” models in patient care.

“Listen and Learn” — But Don’t Stop!

“Listen and Learn” — But Don’t Stop!

A very familiar start! And also a patient-centered start. However, after a patient’s first few sentences, we reach a conversational crossroads and make a decision: either transition to the “history” piece, or explore a little further to find out what really matters to the patient.

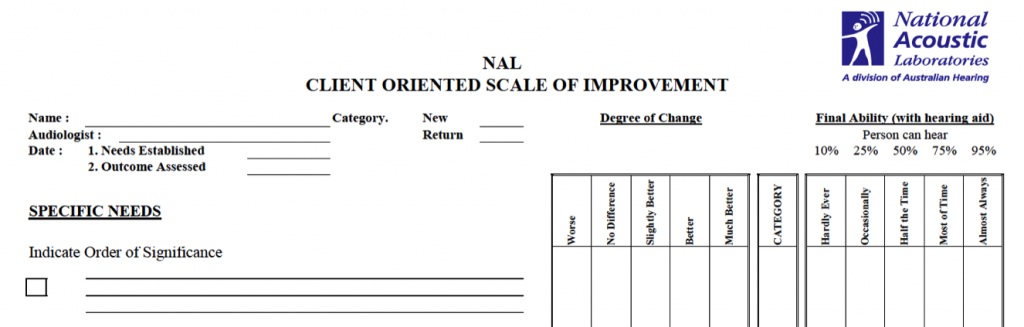

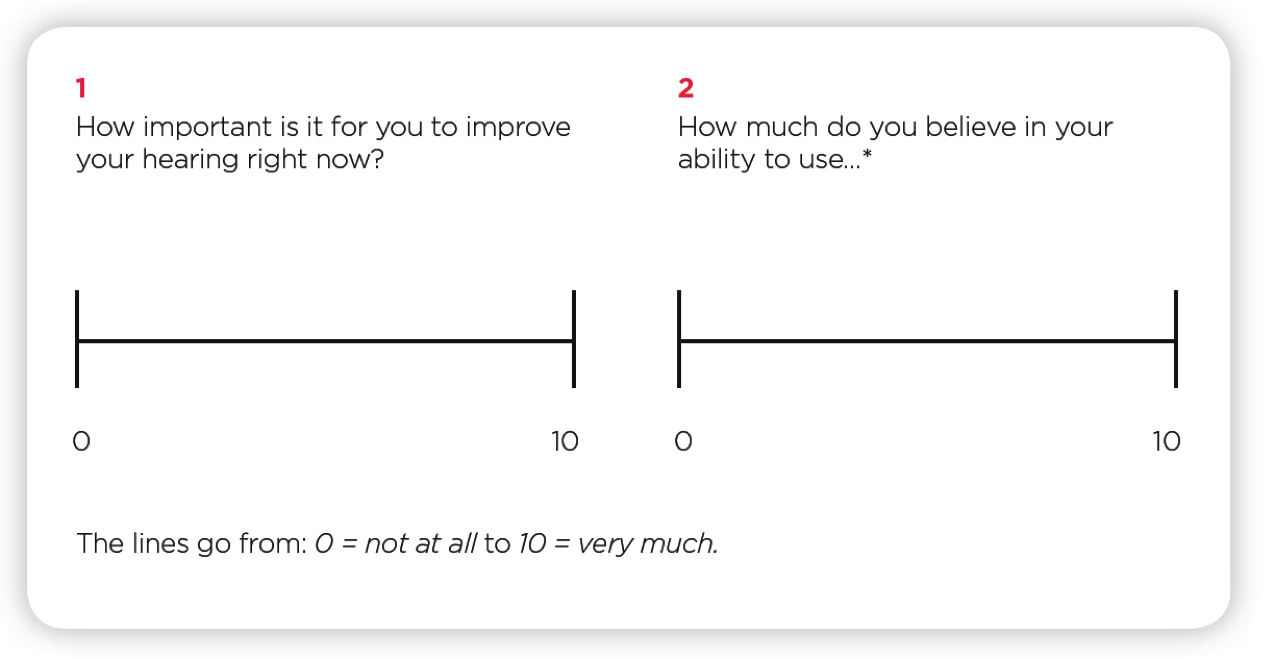

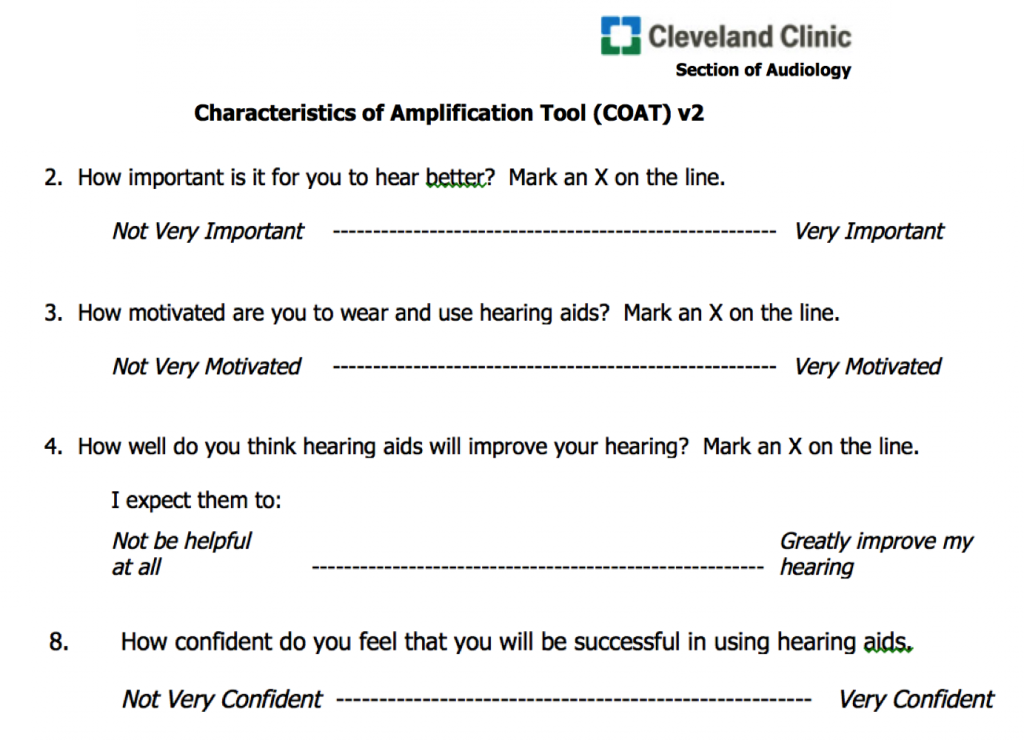

A very familiar start! And also a patient-centered start. However, after a patient’s first few sentences, we reach a conversational crossroads and make a decision: either transition to the “history” piece, or explore a little further to find out what really matters to the patient. Explorer Tip #1: Discussing Self-Assessment Reports

Explorer Tip #1: Discussing Self-Assessment Reports

This entry is the first in a 5-part series designed to compile what we know about PCC in audiology, as well as identify what we don’t know. The next four entries willl explore the concept of patient-centeredness in audiology practices, using Stewart et al.’s (2014) “interactive components” as a framework:

This entry is the first in a 5-part series designed to compile what we know about PCC in audiology, as well as identify what we don’t know. The next four entries willl explore the concept of patient-centeredness in audiology practices, using Stewart et al.’s (2014) “interactive components” as a framework: Laya Poost-Foroosh, PhD., MClSc.

Laya Poost-Foroosh, PhD., MClSc.

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue?

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue?