Hearing Therapist Audiologist

British Society of Hearing Aid Audiologists

Everything we do in our hearing care consultations must have a purpose. Given our daily time crunch, it is a true challenge to purposefully apply person-centred practices such as shared decision making, ownership and rapport – and simultaneously work with the realities of the retail imperative. We need to support the person in the purchase and use of a product that no one wants, all the while working with barriers of stigma, bereavement of selfhood, and limited understanding of hearing instrument technology.

These responsibilities take up a lot of “bandwidth,” and it can be very tempting to resort to habits, shortcuts and routines. Hence the question: can we be person-centred and also sell hearing aids? Following are three ways we can answer with YES.

YES: Begin with Carl Rogers’ Concept of “Person-Centredness”

Psychological therapy was initially based on the professional’s didactic perspective of how therapy should be undertaken and how success would be measured. Rogers was a radical thinker and changed this perspective. He believed that genuine meaningful therapeutic change would only occur when certain core clinician behaviors were applied: empathy, unconditional positive regard (acceptance) and congruence (being genuine)(Rogers, 1961). Specifically:

- The clinician should work alongside the client as an equal partner in the therapeutic intervention;

- By building on ‘unconditional positive regard’ and ‘empathy,’ the client is supported to recognize and acknowledge their own behaviours and responses through ‘congruence’ from the therapist;

- A person’s own life experience provides the basis for their own standards of living in the real world, and influences their acceptance of therapy.

Rather than the therapist controlling the clinical interaction, Rogers explicitly addressed the issue of power and challenged the presumption of expertise. When he was described as “giving power back to the patient,” he insisted on clarifying: “It is not that this approach gives power to the person; it never takes it away” (Rogers, 1977, p. xii).

His theories developed further through psychological research and have become a cornerstone of most current interventions. [Read more about the Rogerian approach here.]

YES: Review Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

YES: Review Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

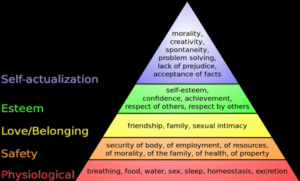

Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers were both considered founders of a humanistic approach to psychology. Maslow’s now-classic pyramid-shaped model (“hierarchy of needs”) reflects five states, starting with the need for sustenance, procreation, and existence, and then for safety and security. When these needs are met, relationships become important, leading to a need to be liked, respected, and to have a place in the group, which allows us to have an identity or self-actualisation; we can be who we choose to be. He later amended and addressed some concerns about this model, but as a concept it remains a useful visual tool.

If we accept that behaviours are based on these needs being met or not met, then we can place Rogerian principles of acceptance, congruence and empathy within this hierarchy as being integral to function within a “normal” life. In other words, a person-centred approach is positioned within the concept of having a “normal life” and being valued as “normal.”

By understanding better where the concept of person-centred services originated, we can appreciate the work required to maintain its principles in our day-to-day practice. By being congruent, empathic and by practicing real reflective listening, we can help people move from denying they have a hearing problem to purchasing and wearing hearing instruments – in effect, achieving a degree of self-actualization by improving a “self” problem. [Read more about Maslow’s theories here.]

YES: Remember that “Change is Hard” – But Achievable

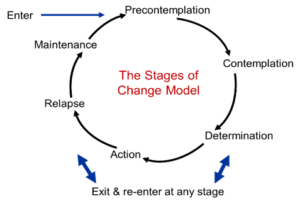

Providing support as recommended by Rogers, and helping a person advance along Maslow’s stages, involves change — which can make people feel uncomfortable, insecure, and off-balance. And yet, people do change, and the process is often described by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983). Developed in the 1980s, this construct helps therapists help their clients understand how and why they behave as they do, and how they could change. TTM is a combination of several ideas examining change and influence, habit and acceptance, and describes the progression through various elements, each having their own response. Anyone who has used the Ida Institute Motivational Tools, or anything similar, will recognise these stages of change pathway as the foundational model. [Read more about TTM here.]

Applying Theory to Practice

These models and theories can be directly contextualized to hearing healthcare and the consultation process. I began this piece by stating that everything we do in the consultation process must have a purpose. Each element of the consultation process must have a solid theoretical and clinical rationale, but embedded within this, each element also should also have a clear commercial perspective.

- The decision to attend the hearing assessment should be rewarded with value within that person’s concept of worth, value and self esteem. They should be able to recognise the empathy and positive regard we as Audiologists afford them.

- They should feel that their time and effort to attend the appointment is worth their while. This implies consequently that our time and effort as audiologists and therapeutic partners, are valuable too. This is a value construct and is a commercial transaction, even if no money has passed between us at this point. People have begun to think about the relationship in a transactional manner: they give us their time, and in return we give them information, advice and professional expertise. This has a tangible value. We go further to establish the need for our expertise, services and, in time, amplification products.

- We ask open questions, eliciting answers where we actively listen, noting salient clues about attitudes, behaviours, needs and expectations which we reflect back, thereby demonstrating empathy. We gather commercially pertinent information in a non-judgmental manner about communication difficulty, domestic and work relationship conflicts, and the relative importance of those communication ecologies.

- The consultation process should also allow us to understand the person’s place on their own cycle of the stages of change. This will help us to support and frame their expectations, work with them to acknowledge and/or accept their hearing loss, and build the desire to make a shared decision to purchase hearing amplification where that’s the most appropriate solution.

Conclusion

As Audiologists, we must maintain an ethical and congruent relationship with the people with whom we work. Understanding the theoretical foundations of a person-centred approach enables us to be effective and efficacious in our relationships, within the parameters of the commercial reality of the retail imperative.

References

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–96.

Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a oerson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Roger, C. (1977). Carl Rogers on personal power. NY: Delacort Press.