David Luterman, D.Ed.

David Luterman, D.Ed.

Professor Emeritus

Emerson College, Boston MA

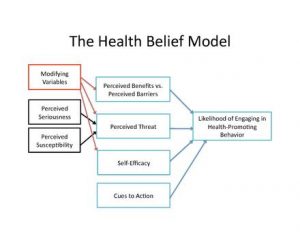

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2018) has delineated two aspects of counseling as within the scope of practice of audiologists: information and personal adjustment. The information aspect of counseling is relatively easy for audiologists to manage as it fits comfortably within the medical model of service delivery and also fits the expectation of clients.

The personal adjustment aspect, on the other hand, often presents difficulty; it means encountering clients on a psychosocial level involving their emotions and in this realm, audiologists often feel a lack of training (Meibos et al., 2017). The discomfort in psychosocial counseling is reflected in several studies: Ekberg, Grenness, and Hickson (2014) analyzed the clinical interactions between audiologists and 63 elderly hearing aid clients. They found that audiologists did not address the clients’ social and emotional needs but continued in content based communication. Cienkowski and Saunders (2013) examined the communication of audiologists during hearing aid fittings, and found that over 66% of the communication was content based. They also concluded that clients would benefit greatly if audiologists became more comfortable with personal adjustment counseling.

“Whole Person Care”

mind + heart

In actual practice, however, there should be no distinction between the informational aspect of counseling and the emotional component. There is considerable research evidence indicating that clients do not retain much content after a diagnostic evaluation (Margolis,2004; Martin, 1990) and the reason for the low retention of content is directly related to their anxiety level (Kessels, 2003). We know this on an experiential level: when we are emotionally upset, our cognitive ability becomes limited. Our brain goes into fight or flight mode and if we try to read something we can read the words, but they do not connect in the brain; we are essentially in our right brain. What this means: if we do not address the emotions of our clients, then information will not be processed. Therefore, to be effective as clinicians, we need to address both content and personal adjustment.

Personal adjustment counseling is often not addressed because it is lacking in training programs (Wicker et al., 2018), and it feels professionally risky to practicing audiologists because there is a lack of structure and no clear guidelines. The primary experience of our clients is grief. They have lost the life they thought they would have, and this is a painful loss. At heart we need to be grief counselors.

In emotion based counseling, clients’ primary need is to be listened to non-judgmentally, not made to feel better. This is a hard concept for professionals to acquire, as our assumed mandate is to fix, and in the personal adjustment realm the fix is not apparent. Our clients are not emotionally disturbed; they are emotionally upset, which is appropriate to their life situation. The conventional response to someone who is upset is to try to make them feel better. The two favorite strategies are to instill hope (“Cochlear implants will make him normal”) or use positive comparisons (“It could be worse. He could have cancer, be deafer, etc.”).

In emotion based counseling, clients’ primary need is to be listened to non-judgmentally, not made to feel better. This is a hard concept for professionals to acquire, as our assumed mandate is to fix, and in the personal adjustment realm the fix is not apparent. Our clients are not emotionally disturbed; they are emotionally upset, which is appropriate to their life situation. The conventional response to someone who is upset is to try to make them feel better. The two favorite strategies are to instill hope (“Cochlear implants will make him normal”) or use positive comparisons (“It could be worse. He could have cancer, be deafer, etc.”).

Neither strategy is effective because it invalidates the client’s emotional pain. Now they feel guilty because they are still upset, and their feeling are stifled. We need to give our clients permission to grieve by listening to them and validating their feelings. We are not putting the feelings in, just giving them permission to be expressed and validated. The notion we need to convey to our clients is that feelings just are; you never have to be responsible for how you feel. Behavior which stems from feelings can be judged as self-enhancing or not. This notion builds in emotional safety for our clients, giving them the permission to express their deep and painful feelings. We have to do nothing but listen and validate and not try to fix or cheer up. I have found that clients self-limit in their emotional expression, and they have their own capacity to make themselves feel better. Embracing painful feelings is the first step in healing. And when this begins to occur, emotions settle down and clients can begin to absorb information. We cannot damage clients by listening and validating their feelings. Giving them information when they are not ready for it can be overwhelming and often diminishes their self-esteem.

Kris English, PhD

Kris English, PhD

should we “go there?” We may think that talking about it will increase a patient’s self-stigma, yet if we don’t talk about it, we can be fairly sure it will not resolve on its own.

should we “go there?” We may think that talking about it will increase a patient’s self-stigma, yet if we don’t talk about it, we can be fairly sure it will not resolve on its own.

John Greer Clark, PhD

John Greer Clark, PhD seems to lose things a lot. His glasses… keys… his watch the other day. We all lose things, but this just seems to be so much more frequent than before. And last week he called me from the grocery parking lot. He said he wasn’t sure if home was to the left or the right from the store. We downsized four years ago and it used to be a right turn out of the lot, but now it’s a left turn. We haven’t really talked to anyone about this. Not yet, anyway.”

seems to lose things a lot. His glasses… keys… his watch the other day. We all lose things, but this just seems to be so much more frequent than before. And last week he called me from the grocery parking lot. He said he wasn’t sure if home was to the left or the right from the store. We downsized four years ago and it used to be a right turn out of the lot, but now it’s a left turn. We haven’t really talked to anyone about this. Not yet, anyway.”

impersonal reassurances, we inadvertently distance ourselves from our patient. We convey access to some special knowledge, that we know more about the situation than the person experiencing it. Such distance-creating signals are inconsistent with what Carl Rogers (1979) called “the subordination of self.”

impersonal reassurances, we inadvertently distance ourselves from our patient. We convey access to some special knowledge, that we know more about the situation than the person experiencing it. Such distance-creating signals are inconsistent with what Carl Rogers (1979) called “the subordination of self.”

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

As for interpersonal awareness: what is our reaction to potentially difficult patient/family conversations? Are we inclined to avoid them altogether, rather than risk opening a “can of worms” (English et al., 2016)? And do we recognize that we signal that reluctance? Or do we convey a willingness to work with them, as this audiologist reported during a workshop:

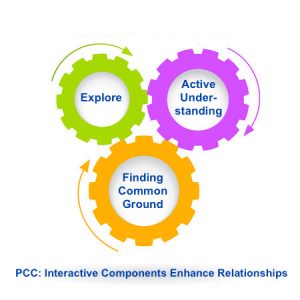

Moving Toward Common Ground

Moving Toward Common Ground

Please note: finding common ground means “mutually influencing each other, each potentially ending up in a place different from where they began, with different understandings than either would have reached alone. It is not a matter of who has power and who does not.” (Stewart et al., 2014, p. 138). (More on

Please note: finding common ground means “mutually influencing each other, each potentially ending up in a place different from where they began, with different understandings than either would have reached alone. It is not a matter of who has power and who does not.” (Stewart et al., 2014, p. 138). (More on

1. I can explain the difference between “informative” and “interpretive” models in patient care.

1. I can explain the difference between “informative” and “interpretive” models in patient care.