Laya Poost-Foroosh, PhD., MClSc.

Laya Poost-Foroosh, PhD., MClSc.

AMS Phoenix Fellow & Research Associate

St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada

Audiologist

Sound Advice Hearing Clinic, Toronto, Canada

Many organizations and healthcare professionals have person-centered aspirations and perceive their model of care to be person-centered. However, the complexities and constraints of actual practice may lead to person-centered moments, occurring in spite of health systems that actually impede person-centered care. As more organizations declare person-centered care as their preferred model of practice, challenges to effectively deploy person-centered care start to emerge. These challenges include both organizational challenges that are embedded in the organizational practice culture and individual challenges associated with lack of adequate training. These challenges could impact how person-centered care is perceived and enacted in different organizations. The following are two examples of encounters that have elements or degrees of person-centered care; however, they result in different outcomes and different care experience by patient.

A Person-Centered Moment

Emily is an 8-year old girl whose teacher suggested her hearing to be tested. Her parents took Emily to see an audiologist. The hearing assessment showed a permanent moderate hearing loss in both ears. When Emily’s parents heard the test results and learned that she needed hearing aids, they were shocked. They were also shocked to hear how much the instruments cost and how much commitment and follow-up it would take to manage Emily’s hearing needs. They felt the audiologist was kind and thorough with testing; she spent one full hour with them and explained the test results and hearing aid options and why it was important for Emily to use hearing aids. She also provided different hearing aid options. However, all of the options were beyond their budget, so they told the audiologist they needed to think about it. They left the clinic without any immediate treatment plans.

seeking “an emotional engagement with the patient that goes beyond sharing information” (Stewart et al., 2014, p. 10)

A Person-Centered Culture

This scenario has played out differently in another setting. In the second setting, Emily’s audiologist recommended hearing aids and Emily’s parents showed some hesitation to follow up with the recommendation. However, in this scenario the audiologist did not want them to leave without knowing what the source of their hesitation was. The audiologist did not know what the issue was; were the parents shocked with the news and needing more time to process it? Was the issue the stigma associated with wearing hearing aids? Or were there concerns with the cost of the intervention? So, she spent more time to get to know Emily and her family. She learned that there were some concerns with Emily’s hearing when she was younger but her parents did not take it seriously because Emily started talking, reading, and writing in line with typical developmental expectations.

They also thought the reason that Emily did not socialize in school like other kids her age was because she was shy. They did not attribute Emily’s poor academic performance to her hearing because they were never academically strong themselves. Emily’s dad works in a bakery and her mom has a part time job with minimum wage. Emily has three siblings ranging in age from 3 to 11.

After taking the time to get to know the family better, the audiologist realized the reason for Emily’s parents’ hesitation was a complex mix of guilt, regret, and frustration. While their most tangible concern was the cost associated with getting hearing aids, they also felt regret for not having noticed or acted sooner, and could not help but wonder if Emily had missed out on academic and social development over the years as a result of their own failings.

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue?

…the patient (or parent) breaks eye contact. She looks at the floor, or her hands, or the door (no mystery what that likely means), or at nothing in particular. Do we notice? If we notice, do we pause? Or do we keep talking and ignore the nonverbal cue?

Jeanine Doherty, Au.D., M.Phil., M.B.S, B.Soc.Sci.(Hons.)

Jeanine Doherty, Au.D., M.Phil., M.B.S, B.Soc.Sci.(Hons.)

John Greer Clark, PhD

John Greer Clark, PhD professions in many ways. I am sure that we are not unique in the dilemma that classroom teaching does not always reflect what students practice in their clinical settings. In the 1960s and 1970s we ardently argued that the full management of hearing loss, including the dispensing of products to assist those with hearing deficits, could indeed be done ethically. And we argued that we were the best prepared to provide this service and that we could do it better. I do believe we are better prepared and can fully service those with hearing loss more effectively than other hearing health care professions. However, it is dismaying that we largely adopted the dispensing practices already in place and have not substantially deviated from these over the years to incorporate better use of personal adjustment counseling and to address more fully the rehabilitative needs of patients.

professions in many ways. I am sure that we are not unique in the dilemma that classroom teaching does not always reflect what students practice in their clinical settings. In the 1960s and 1970s we ardently argued that the full management of hearing loss, including the dispensing of products to assist those with hearing deficits, could indeed be done ethically. And we argued that we were the best prepared to provide this service and that we could do it better. I do believe we are better prepared and can fully service those with hearing loss more effectively than other hearing health care professions. However, it is dismaying that we largely adopted the dispensing practices already in place and have not substantially deviated from these over the years to incorporate better use of personal adjustment counseling and to address more fully the rehabilitative needs of patients. Every Patient’s Story Matters

Every Patient’s Story Matters Georgina Aidoo

Georgina Aidoo usually does not command much attention in third world countries, even though various studies and estimates indicate that two-thirds of the world’s populations of hearing impaired people live in the developing countries. In many African countries, the general awareness of Audiology and hearing loss management is low, and lack of resources, ignorance, illiteracy, cultural diversity and national priorities among many other factors relating to technology enhancement and sense of focus has caused a lack of strong advocacy in this area. The Africa continent has a predominantly young population and many are at risk of getting diseases causing hearing loss (McPherson & Holboro, 1985). Overall, it is estimated that in the countries below Sahara, more than 1.2 million children aged between 5 and 14 years suffer from moderate to severe hearing loss in both ears. General prevalence studies show higher rates of severe to profound hearing loss in this part of Africa than in other developing countries.

usually does not command much attention in third world countries, even though various studies and estimates indicate that two-thirds of the world’s populations of hearing impaired people live in the developing countries. In many African countries, the general awareness of Audiology and hearing loss management is low, and lack of resources, ignorance, illiteracy, cultural diversity and national priorities among many other factors relating to technology enhancement and sense of focus has caused a lack of strong advocacy in this area. The Africa continent has a predominantly young population and many are at risk of getting diseases causing hearing loss (McPherson & Holboro, 1985). Overall, it is estimated that in the countries below Sahara, more than 1.2 million children aged between 5 and 14 years suffer from moderate to severe hearing loss in both ears. General prevalence studies show higher rates of severe to profound hearing loss in this part of Africa than in other developing countries. The case of Ghana is no different. In spite of the fact that hearing and balancing disorders are common among persons in communities in Ghana, very few studies have been carried out. The pace of development is very slow despite how critical the need is.

The case of Ghana is no different. In spite of the fact that hearing and balancing disorders are common among persons in communities in Ghana, very few studies have been carried out. The pace of development is very slow despite how critical the need is. Karen Muñoz, EdD

Karen Muñoz, EdD

just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes.

just like other skills in audiology such as completing a diagnostic test or troubleshooting hearing aids. Teaching counseling in our graduate training programs needs to be approached from an evidence-based perspective. Audiology would benefit from clear evidence-based counseling guidelines that provide a consistent message about the purpose, indicate needed knowledge and skills, and training considerations for classroom and clinical experiences. Teaching counseling in audiology is in need of attention and further research to improve educational practices, implementation of skills, and most importantly, to positively influence client and family outcomes. Judith Blumsack, PhD

Judith Blumsack, PhD

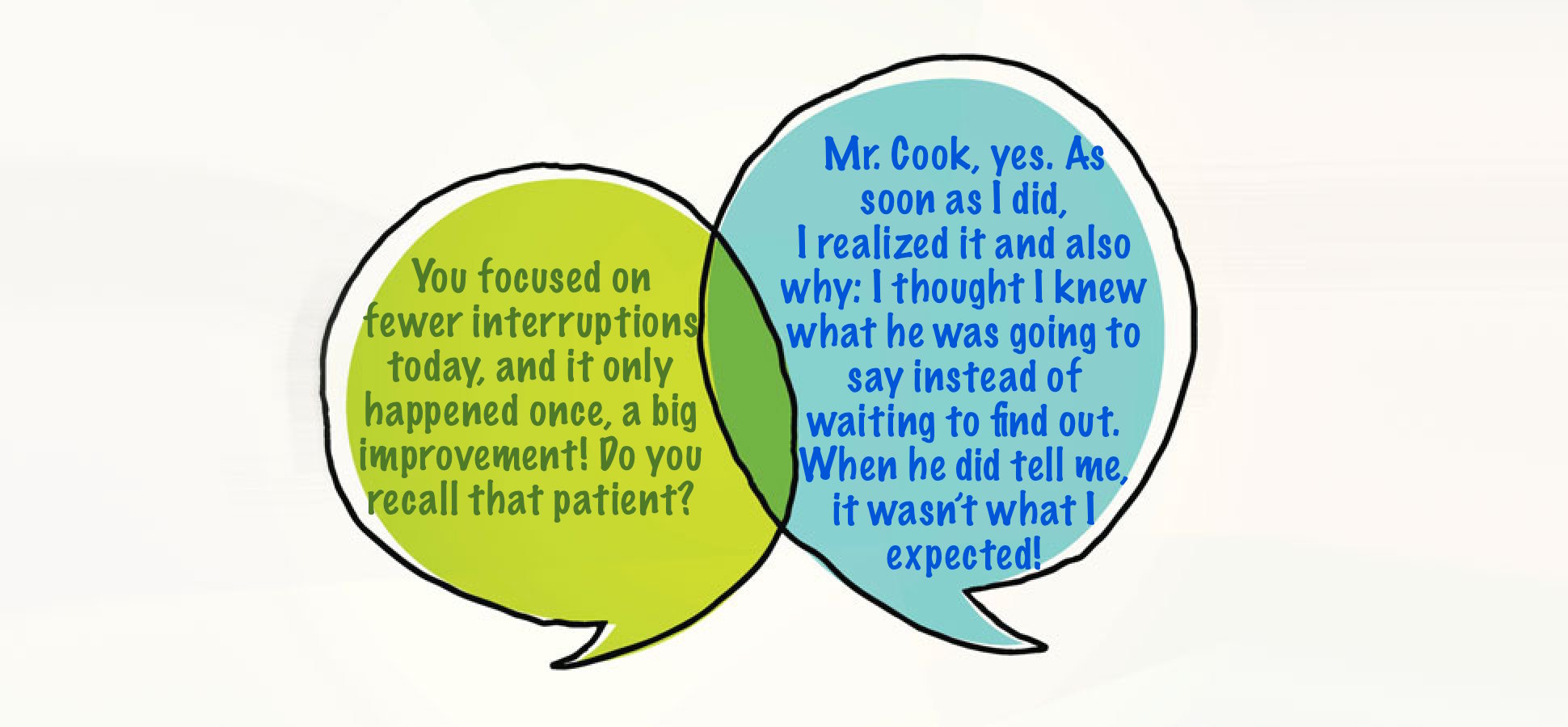

There was no terminology for my approach at the time, but now I know it can be called audiologist-centered (i.e., it was all about me). Consistent with my quiz answers, I expected to direct the appointment, while the patient passively followed my lead. I didn’t intend to be disrespectful or dismissive of the patient’s role, but I held a naïve (some would say paternalistic) assumption that patients had no say because they didn’t know what I knew, and I knew best. In reality, of course adult patients are anything but passive: they are autonomous beings and they will make decisions with or without our involvement (Tauber, 2005).

There was no terminology for my approach at the time, but now I know it can be called audiologist-centered (i.e., it was all about me). Consistent with my quiz answers, I expected to direct the appointment, while the patient passively followed my lead. I didn’t intend to be disrespectful or dismissive of the patient’s role, but I held a naïve (some would say paternalistic) assumption that patients had no say because they didn’t know what I knew, and I knew best. In reality, of course adult patients are anything but passive: they are autonomous beings and they will make decisions with or without our involvement (Tauber, 2005).

When we examine this “auto-pilot” practice, even more questions emerge. What would happen if we do give patients a choice, and ask if they would prefer a “big picture” summary or the details? If they choose “big picture summary,” will we freeze up? Do we use the audiogram as a prop, or can we put our test results to one side, use simple terms to clearly relate the findings to their initial concerns, and move on?

When we examine this “auto-pilot” practice, even more questions emerge. What would happen if we do give patients a choice, and ask if they would prefer a “big picture” summary or the details? If they choose “big picture summary,” will we freeze up? Do we use the audiogram as a prop, or can we put our test results to one side, use simple terms to clearly relate the findings to their initial concerns, and move on? The Impact of Labels

The Impact of Labels